Postherpetic Neuralgia: What It Is and How to Manage It

If you’ve ever had shingles, you know the rash can be painful. For some people the pain doesn’t go away when the skin heals. That lingering ache is called postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). It’s a nerve problem that sticks around weeks, months, or even years after the shingles rash disappears.

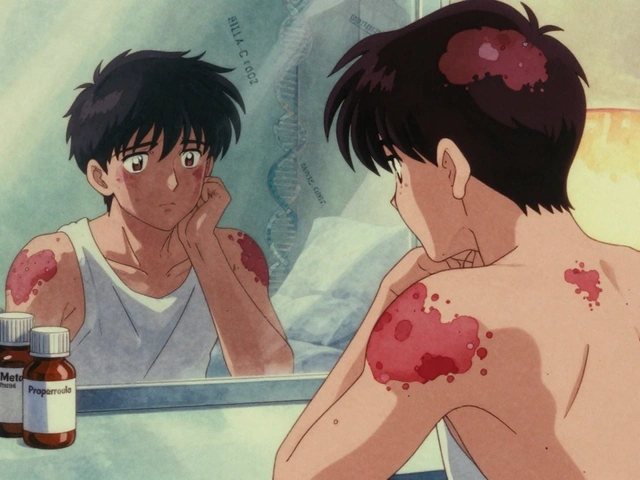

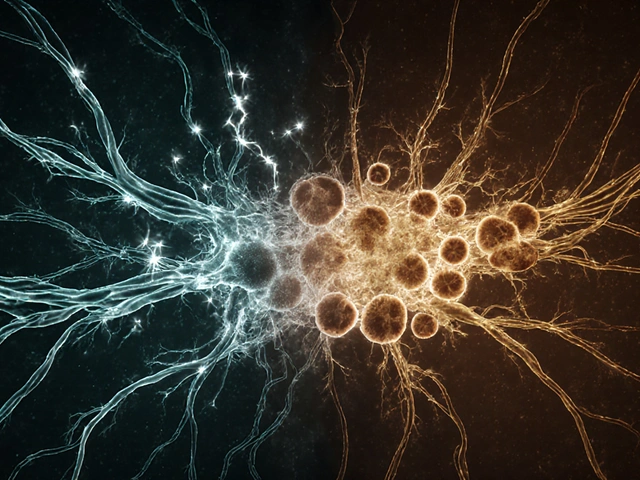

PHN happens because the varicella‑zoster virus, the same virus that gives you chickenpox, attacks nerves in the skin. When the virus reactivates as shingles, it damages those nerves. Even after the virus stops, the nerves may stay irritated, sending pain signals to the brain.

Why the Pain Lingers

The exact reason isn’t fully understood, but doctors think two things are at play. First, the virus causes inflammation that harms the protective myelin sheath around the nerve. Without that sheath, the nerve sends mixed signals—pain, tingling, or burning sensations. Second, the damaged nerves can become “hyper‑active,” meaning they fire even when there’s no real threat.

Age is a big risk factor. People over 60 are more likely to develop PHN because their nerves recover slower. A severe shingles outbreak, especially on the torso or face, also raises the odds. If you had a weak immune system during the shingles episode, your chances go up, too.Typical symptoms include a burning or stabbing pain in the area where the rash was, heightened sensitivity to touch (even clothing can feel harsh), and sometimes itching or numbness. The pain can be constant or flare up unexpectedly, making daily activities tough.

Practical Relief Options

Good news: there are several ways to calm the nerve pain. Most doctors start with medications that target nerve signals. These include gabapentin, pregabalin, and certain antidepressants like amitriptyline. They don’t treat the virus, but they dull the nerve’s chatter.

Topical treatments work well for many. A lidocaine patch applied to the painful spot can numb the area without affecting the rest of your body. Capsaicin cream, made from chili peppers, may sound odd, but it depletes a chemical that nerves use to send pain signals.

If oral meds aren’t enough, a doctor might suggest a short course of steroids to reduce lingering inflammation, or even a nerve block—an injection that numbs the affected nerves for a few weeks.

Non‑drug approaches also help. Gentle skin massage, warm compresses, and regular low‑impact exercise improve blood flow and can reduce sensitivity. Some people find relief with acupuncture or TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) devices that send mild electric pulses to the skin.

Vaccination is a preventive step. The shingles vaccine (Shingrix) dramatically cuts the risk of both shingles and PHN. If you’re over 50, talk to your doctor about getting the shot.

Living with PHN can feel frustrating, but combining medication, topical creams, and lifestyle tweaks often brings noticeable improvement. Keep a pain diary to track what works best for you, and don’t hesitate to ask your doctor about adjusting the treatment plan. With the right approach, the nagging nerve pain can become a manageable part of life rather than a constant burden.

How Postherpetic Neuralgia Links to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

By Lindsey Smith On 26 Sep, 2025 Comments (15)

Explore the biological overlap between postherpetic neuralgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, covering shared mechanisms, symptoms, and treatment strategies in a clear, evidence‑based guide.

View More