Most people think patents are the only thing protecting a drug from generic competition. But that’s not true. In reality, market exclusivity extensions often matter more than patents themselves. A drug can lose its patent and still stay off the market for years - not because of legal barriers, but because of regulatory rules built into the system. These aren’t loopholes. They’re official, congressionally approved tools designed to encourage innovation. But today, they’re being used to stretch monopolies far beyond what anyone originally intended.

How Market Exclusivity Works - Beyond Patents

Patents give you 20 years of protection from the day you file. But for drugs, that clock starts ticking long before the product even hits shelves. Clinical trials take 7-10 years. The FDA review adds another 1-3. By the time a drug is approved, you might have only 7-10 years left on your patent. That’s not enough to recoup billions spent on R&D. So Congress created market exclusivity extensions - separate from patents - to make up for lost time. These aren’t just bonuses. They’re legal barriers. Even if a patent expires, generic makers can’t launch until the exclusivity period ends. And unlike patents, which can be challenged in court, these exclusivities are granted by regulators and are nearly impossible to fight. The FDA doesn’t care if a generic version is identical. If the clock hasn’t run out, they won’t approve it.The Five Main Types of Exclusivity in the U.S.

The U.S. system has five key types of market exclusivity, each with different rules and durations:- New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity - 5 years. This applies to drugs with an active ingredient never approved before. No generics allowed during this time, even if the patent is expired.

- Orphan Drug exclusivity - 7 years. For drugs treating diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 Americans. This one’s powerful because it doesn’t require a patent. Even if the compound is off-patent, no other company can market the same drug for the same rare disease.

- New Clinical Investigation exclusivity - 3 years. For new uses, formulations, or dosages of existing drugs. But here’s the catch: the FDA now demands proof of clinical superiority. You can’t just tweak the pill and call it new.

- Pediatric exclusivity - 6 months added to any existing exclusivity. To get it, companies must complete FDA-requested studies on children. It’s not free money - it’s a trade. But for blockbuster drugs, 6 months can mean over $1 billion in extra revenue.

- Patent Challenge exclusivity - 180 days for the first generic to challenge a patent successfully. This is a race. Only one generic gets it, and they’re the only ones allowed to sell during that window.

What makes this system dangerous is stacking. A drug can have NCE exclusivity (5 years), then pediatric extension (6 months), then orphan status (7 years), then 3-year exclusivity for a new use. These don’t replace each other - they pile up. One drug might have 15+ years of protection without a single patent left.

How the EU Does It Differently

Europe doesn’t use the same patchwork. Instead, they have the Supplemental Protection Certificate (SPC), which extends patent life up to 15 years after approval. It’s simpler, but still powerful. The EU also offers 10 years of market exclusivity for orphan drugs - extended to 12 if the company does pediatric studies. That’s longer than the U.S. version. But here’s the twist: the EU doesn’t allow stacking the same way the U.S. does. You can’t combine multiple exclusivities on one drug unless they’re tied to different conditions. The U.S. system is more flexible - and more exploitable. A company can file for orphan status, then a new indication, then pediatric extension - all on the same molecule - and get 5 + 3 + 6 months = 8.5 years of extra protection, even after the patent dies.

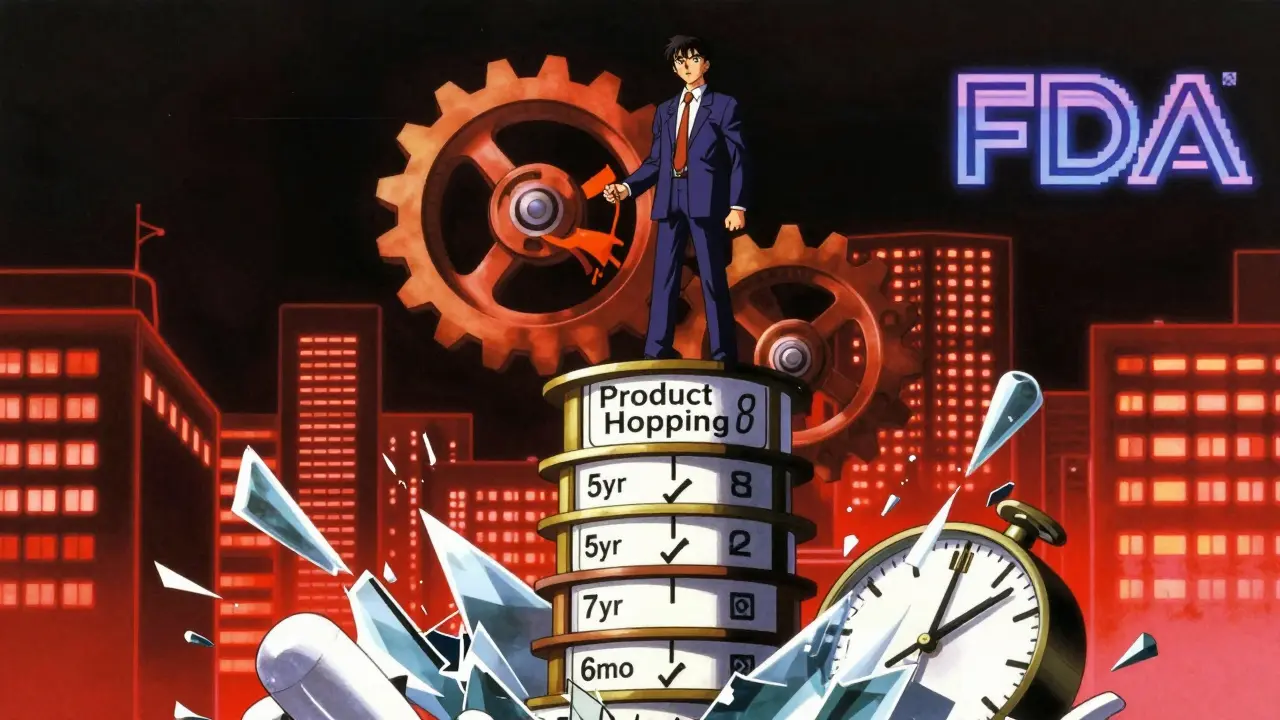

Product Hopping and the Patent Thicket

Companies don’t just wait for exclusivity to expire. They actively delay generics. One common trick is called product hopping. Just before a patent runs out, they launch a slightly modified version - maybe a pill that dissolves faster, or a new delivery method. Then they convince doctors and insurers to switch to the new version. Generics can’t copy it until the new formulation’s exclusivity runs out. Teva reported in 2022 that this tactic delayed generic entry for 17% of their target drugs. Even worse is the patent thicket. Instead of one patent, companies file dozens. A drug called tazarotene had 48 secondary patents covering everything from tablet coatings to dosing schedules. None of these patents were about the drug’s core function - they were all about slowing down competitors. The FDA can’t reject these patents. Only courts can. And court battles take years.Why This System Exists - And Why It’s Broken

The original goal was simple: reward real innovation. If you develop a drug for a rare disease, or prove it works in children, you deserve extra time. That makes sense. But today, the system rewards manipulation more than breakthroughs. Take orphan drugs. In 2010, only 201 drugs had orphan status. By 2022, that number jumped to 1,027 - nearly 40% of all new approvals. Many of these drugs treat conditions that aren’t rare at all. Some are repurposed versions of common medications with minor tweaks. The FDA still grants the exclusivity because the law doesn’t require proof of medical necessity - only a patient count. And the financial impact? A 2023 study in JAMA Health Forum found that just four drugs - bimatoprost, celecoxib, glatiramer, and imatinib - cost the U.S. healthcare system an extra $3.5 billion over two years because exclusivity blocked generics. That’s not innovation. That’s rent-seeking.

Who Benefits - And Who Pays

The winners are big pharma. Companies like Bristol Myers Squibb and Novartis have teams of 20+ lawyers and regulatory experts whose only job is to extend exclusivity. They file patents strategically - waiting until after Phase II trials to lock in the 20-year clock. They time their orphan applications to coincide with patent expirations. They push for pediatric studies not because children need the drug, but because the 6-month extension is worth billions. The losers? Patients. Insurers. Taxpayers. Generic manufacturers who can’t enter the market. And small biotechs who can’t afford the legal battles. A 2023 BIO survey found 68% of startups rely on exclusivity to attract funding. But that means innovation is being judged by how well you game the system, not how good your drug is.What’s Changing - And What’s Next

Regulators are starting to push back. In April 2023, the FDA tightened rules for 3-year exclusivity, demanding stronger proof of clinical benefit. The FTC filed an amicus brief in June 2023 arguing that product hopping violates antitrust laws. The European Commission is reviewing the SPC system to stop minor modifications from getting extra time. But the real change will come from pressure. Patient groups are speaking up. Economists are publishing data. And generics makers are getting smarter. In 2024, a court ruled that a drug’s pediatric exclusivity couldn’t be extended if the studies were done in adults only. That was a landmark. By 2028, experts predict the average drug will have 16.3 years of market exclusivity - up from 12.7 in 2018. That’s not innovation. That’s a system rigged for delay.What This Means for You

If you’re a patient, understand that your drug’s high price isn’t just about R&D. It’s about legal strategy. If you’re a student or professional in pharma, learn these mechanisms - they’re the hidden engine of the industry. If you’re a policymaker, ask: Is this system still serving its original purpose? Or has it become a tool for profit at the cost of access? The truth is simple: patents are just the beginning. Market exclusivity extensions are where the real monopoly begins - and where the fight for affordable medicines is truly being fought.What’s the difference between a patent and market exclusivity?

A patent is a legal right granted by the USPTO that protects the invention itself - usually the chemical compound. It lasts 20 years from filing. Market exclusivity is a regulatory protection granted by the FDA that blocks generic versions from being approved, regardless of patent status. It’s based on the type of drug and the data submitted, not the invention. You can have exclusivity without a patent, and vice versa.

Can a drug have both a patent and exclusivity at the same time?

Yes, and most do. In fact, it’s standard practice. A drug might have a core patent expiring in 2030, NCE exclusivity until 2028, pediatric exclusivity extending that to 2028.5, and orphan status until 2035. The exclusivities stack, and generics can’t enter until the last one expires - even if the patent is already dead.

Why do companies file so many secondary patents?

To create a "patent thicket." Each patent covers a minor change - like a new coating, a different dosage form, or a specific dosing schedule. Even if the core compound is off-patent, generics can’t launch without infringing one of these secondary patents. It’s not about protecting innovation. It’s about legal obstruction.

Is pediatric exclusivity really about children’s health?

Sometimes. But often, it’s a financial move. The FDA requires studies on children to get the 6-month extension, but those studies aren’t always medically necessary. Many are done on adults first, then replicated in kids. The real incentive isn’t pediatric care - it’s the extra time to charge monopoly prices. That’s why some experts call it a "regulatory loophole disguised as public health policy."

How do generic manufacturers fight these extensions?

They challenge patents in court, file citizen petitions to question FDA decisions, and use the 180-day exclusivity window when they’re first to challenge. But it’s expensive and slow. Many smaller generics can’t afford the legal battle. That’s why only a handful of companies dominate the generics market - they’re the only ones with the resources to outlast the exclusivity game.

Jacob Hill

January 18, 2026 AT 21:42Wow, this is such a well-researched breakdown-I’ve been following this for years, and you nailed it. The stacking of exclusivities is insane; I once tracked a drug that had 19 years of protection-no patent left, but still no generics. It’s not innovation, it’s a legal shell game.

Jackson Doughart

January 19, 2026 AT 19:13While I appreciate the depth of this analysis, I must respectfully note that the system, however flawed, was designed with legitimate intent: to incentivize high-risk pharmaceutical development. To dismantle these mechanisms without viable alternatives may inadvertently stifle the very innovation that saves lives.

Tracy Howard

January 20, 2026 AT 04:17Of course the U.S. system is a mess-can you believe they let companies game orphan drug status like it’s a tax loophole? In Canada, we don’t let Big Pharma turn rare diseases into cash cows. This isn’t healthcare, it’s corporate theater with FDA approval stamps.

Valerie DeLoach

January 20, 2026 AT 04:54This is one of those topics that reveals how deeply our systems have been colonized by profit motives disguised as public policy. We tell ourselves we’re rewarding innovation, but we’re really rewarding legal ingenuity. The real tragedy? The people who need these drugs most are the ones paying the highest price-for nothing but delay.

Christi Steinbeck

January 20, 2026 AT 19:00STOP letting them get away with this. Every day we wait, someone can’t afford their insulin. Every 6-month extension is a death sentence for someone without insurance. We have the power to change this-vote, protest, call your reps. This isn’t politics, it’s survival.

sujit paul

January 22, 2026 AT 13:47Let me tell you something... this is not accidental. The entire pharmaceutical-industrial complex is a controlled operation. The FDA, Congress, even the WHO-they are all part of a global system designed to keep medicines expensive. The real cure? A complete overhaul of the monetary system. You think this is about drugs? No. It's about control.

Aman Kumar

January 23, 2026 AT 12:34The patent thicket strategy is textbook rent-seeking behavior-exploiting regulatory arbitrage through procedural obfuscation. The FDA’s passive complicity in enabling this constitutes a systemic failure of fiduciary duty to the public interest. We are witnessing institutional capture at scale.

Jake Rudin

January 24, 2026 AT 21:05It’s wild how we celebrate patents as innovation… but ignore that the real monopoly power comes from the FDA’s bureaucracy. The patent’s just the headline. The exclusivity extensions? That’s the whole damn article. And no one’s talking about it.

Lydia H.

January 25, 2026 AT 16:01I used to think generics were just cheaper copies. Now I see they’re the only thing keeping people alive. And companies are literally building legal walls to stop them. That’s not business. That’s cruelty dressed up as policy.

Astha Jain

January 27, 2026 AT 00:16lol at the FDA being fooled by 'new formulations'... like a pill that dissolves 0.2 seconds faster? Come on. This system is a joke. And the 6-month pediatric extension? More like a 6-month profit bonus for CEOs.

Phil Hillson

January 27, 2026 AT 08:07So what? Pharma makes money. People get drugs. If you can't afford it, get a better job. This whole post is just a cry for handouts disguised as reform. Wake up.