Every time you take an antibiotic when you don’t need it, you’re not just helping yourself-you’re helping bacteria become stronger. That’s the harsh truth behind antibiotic resistance, a quiet crisis that’s already killing over 1.27 million people each year worldwide. It’s not science fiction. It’s happening right now, in hospitals, farms, and even your own home. And the reason? Bacteria are evolving faster than we can keep up.

How Bacteria Outsmart Antibiotics

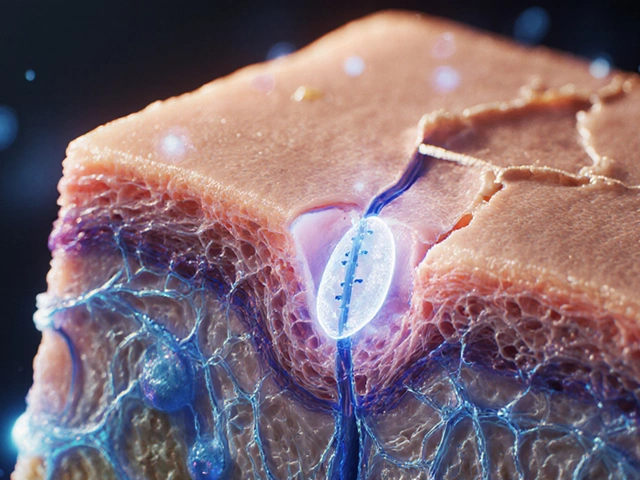

Antibiotics were supposed to be magic bullets. Penicillin, discovered in 1928, saved millions. But even its discoverer, Alexander Fleming, warned that misuse would lead to resistance. He was right. Today, bacteria don’t just survive antibiotics-they learn how to defeat them.Bacteria don’t think, but they do mutate. And when they do, some changes give them an edge. These aren’t random accidents-they’re survival tricks honed by natural selection. The most common tricks include:

- Building thicker walls to block antibiotics from getting in

- Spitting antibiotics back out using molecular pumps

- Changing the target inside their cells so the drug no longer fits

- Breaking down antibiotics with enzymes

- Switching to completely different metabolic pathways

Research from 2024 tracked six bacterial strains from the food chain as they were slowly exposed to increasing doses of antibiotics. All of them became resistant. Not just a little resistant-some needed over six times the original dose to be killed. And the mutations weren’t steady. At first, bacteria used temporary tricks like DNA methylation to survive. Later, they locked in those changes with permanent genetic mutations. By generation 150 in dynamic conditions, resistance was already strong. In static conditions, it took over 500 generations.

The Genes Behind the Resistance

Some genes are repeat offenders when it comes to resistance. Mutations in fusA, gyrA, and parC show up again and again across different bacteria. For example, mutations in the ampC gene are almost always linked to amoxicillin resistance. For cefepime, it’s the pbp genes that change.What’s surprising is how much the genetic landscape shifts over time. Early on, you might see dozens of mutations. But by the end, only 8% to 20% of those original mutations stick around. The rest are replaced. It’s like the bacteria are testing out different tools, keeping only the ones that work best.

Tetracycline resistance is a perfect example of this complexity. It doesn’t come from one mutation. It comes from two working together. First, a transposon-a kind of jumping gene-inserts itself near the acrB gene and flips a switch, turning on a pump that kicks out the drug. Then, later, mutations in the acrB gene itself make that pump even better. Neither change alone would be enough. Together, they create a powerful defense.

It’s Not Just Antibiotics

You might think only antibiotics cause resistance. But that’s not true. New research shows that common non-antibiotic drugs-like painkillers, antidepressants, and even some heart medications-can help spread resistance genes between bacteria. These drugs don’t kill bacteria, but they create stress. And stressed bacteria are more likely to pick up foreign DNA from their environment, including resistance genes from other bugs.This is a game-changer. It means resistance isn’t just a problem in hospitals or farms. It’s in our water, our soil, and even our sewage. A single pill you flush down the toilet could be feeding resistance in a river miles away.

Why We’re Losing the Battle

In the U.S., about 30% of outpatient antibiotic prescriptions are unnecessary. That’s 47 million courses of antibiotics every year given to people who don’t need them-for colds, flu, or viral sore throats. Antibiotics don’t work on viruses. But patients ask for them. Doctors give them. And bacteria get stronger.In the EU, antibiotic resistance causes around 33,000 deaths a year and costs €1.5 billion in healthcare and lost productivity. In low-income countries, the problem is worse. Many don’t have the labs to test which antibiotics will work. So doctors guess. And guess wrong. That means more wrong prescriptions, more resistance, and more deaths.

Even when we do have the right drugs, we’re running out. Of the 67 new antibiotics currently in development, only 17 target the most dangerous superbugs. And only 3 are truly new-meaning they can beat existing resistance. The rest are old drugs with minor tweaks. That’s not enough.

What Can You Do?

You don’t need to be a scientist to help stop antibiotic resistance. Here’s what actually works:- Don’t ask for antibiotics for colds or flu. These are viral. Antibiotics won’t help, and they’ll hurt.

- Take antibiotics exactly as prescribed. Don’t skip doses. Don’t stop early, even if you feel better. Leaving even a few bacteria alive lets them evolve.

- Never share antibiotics. What works for one person might be the wrong drug-or the wrong dose-for another.

- Don’t save leftover antibiotics. Store them? No. Use them later? No. Dispose of them properly through pharmacy take-back programs.

- Ask your doctor: “Is this antibiotic really necessary?” Most doctors are willing to explain why they’re prescribing-or not prescribing-a drug.

What’s Being Done?

The good news? People are fighting back. The WHO, FAO, and OIE launched the One Health approach-recognizing that human, animal, and environmental health are all connected. You can’t fix resistance in hospitals if it’s growing in livestock or polluted rivers.More than 150 countries now have national action plans to fight resistance. But execution varies wildly. High-income countries are hitting 75% of their goals. Low-income ones? Only 35%. That gap is deadly.

Scientists are exploring new tools too. CRISPR gene editing can target and destroy resistance genes inside bacteria. New diagnostic tools can identify resistant strains in hours, not days. And machine learning models are learning to predict which mutations will appear next-giving us a chance to stay ahead.

The FDA recently updated testing standards for cefiderocol, a last-resort antibiotic, to better track resistance in carbapenem-resistant bacteria. That’s progress. But it’s still reactive. We need to be proactive.

The Future Is in Our Hands

The World Bank warns that if we do nothing, antibiotic resistance could push 24 million more people into extreme poverty by 2050. The economic cost? Over $1 trillion a year. That’s not a future scenario. It’s a forecast based on current trends.But we’re not powerless. Every time you choose not to take an antibiotic you don’t need, you’re slowing the spread. Every time you finish your full course, you’re killing off the toughest survivors. Every time you ask your doctor why they’re prescribing something, you’re helping them make better choices.

Antibiotics saved our grandparents. But they won’t save our children unless we change how we use them. This isn’t about fear. It’s about responsibility. The bacteria aren’t the enemy. Our misuse is.

The clock is ticking. But it’s not too late.

Can you get antibiotic resistance from taking antibiotics too often?

No-you don’t become resistant. Bacteria do. Every time you take an antibiotic, you kill off the weak bacteria. But if even a few survive-because the dose was too low, or you stopped early-they multiply. Those survivors carry resistance genes. Over time, those genes spread through the population. So it’s not you that becomes resistant. It’s the bacteria around you.

Do probiotics help prevent antibiotic resistance?

Not directly. Probiotics can help restore gut bacteria after antibiotics and reduce side effects like diarrhea, but they don’t stop resistance from developing. Resistance spreads through DNA mutations and gene sharing between bacteria, not through gut balance. Taking probiotics won’t make antibiotics work better or stop superbugs from forming.

Why don’t we just make new antibiotics?

It’s expensive, risky, and slow. Developing a new antibiotic costs over $1 billion and takes 10-15 years. Most pharmaceutical companies focus on drugs for chronic conditions-like diabetes or high blood pressure-because those are more profitable. Antibiotics are used for short periods, and doctors are told to use them sparingly. That makes them poor business. Only 3 of the 67 antibiotics in development today are truly new enough to beat current resistance.

Is antibiotic resistance only a problem in hospitals?

No. In fact, most resistance starts outside hospitals. Up to 70% of antibiotic use happens in agriculture-livestock, poultry, and fish farming. Bacteria from farms spread through soil, water, and food. Even in homes, flushing old antibiotics down the toilet pollutes water systems. Resistance is everywhere: in rivers, in soil, in your kitchen sink. That’s why One Health-the idea that human, animal, and environmental health are linked-is so important.

Can you catch antibiotic-resistant infections from other people?

Yes. Resistant bacteria spread just like regular infections-through coughs, dirty hands, contaminated food, or surfaces. A person carrying MRSA (a resistant staph infection) can pass it to others. Hospitals are hotspots, but so are schools, gyms, and public transport. That’s why handwashing and staying home when sick aren’t just about flu-they’re about stopping superbugs too.

DHARMAN CHELLANI

January 29, 2026 AT 07:33antibiotics r just a scam by big pharma anyway. they want us sick so we keep buying pills. also, your 'science' is just corporate propaganda. 🤡

Kacey Yates

January 31, 2026 AT 00:21Stop taking antibiotics for viral infections. Seriously. It's not rocket science. And stop hoarding leftovers like they're gold. You're not a survivalist, you're a walking resistance factory.

Pawan Kumar

February 1, 2026 AT 15:34One must observe, with profound intellectual rigor, that the emergent phenomenon of antimicrobial resistance is not merely a biological occurrence, but a systemic failure of epistemological frameworks in public health governance. The mutation trajectories observed in fusA and gyrA are not random-they are the logical outcome of neoliberal bioeconomics, wherein profit imperatives override evolutionary ethics. The WHO's One Health initiative, while rhetorically elegant, remains institutionally neutered by capitalist structural constraints. We are witnessing not resistance, but the inevitable collapse of anthropocentric hegemony over microbial life.

Furthermore, the normalization of pharmaceutical consumption as a cultural ritual-particularly in the Global South-reflects a deeper pathology: the internalization of colonial biomedical authority. Your suggestion to 'ask your doctor' is, frankly, naive. Doctors are agents of a system that profits from your compliance. The real solution lies in decentralized, community-based microbiome stewardship-beyond the clinic, beyond the pill.

And let us not ignore the epistemic violence of the FDA's 'reactive' testing protocols. These are not safeguards-they are post-hoc damage control mechanisms designed to preserve institutional legitimacy, not public health. CRISPR-based gene editing? A fascinating toy for the elite. Meanwhile, the rivers of Punjab and the livestock pens of Uttar Pradesh are becoming gene banks of doom, and no one in Geneva dares to speak of it.

Do not mistake this for fear. This is diagnosis. And diagnosis, unlike antibiotics, cannot be prescribed. It must be lived.

Keith Oliver

February 3, 2026 AT 11:42Bro, I got prescribed amoxicillin for a sinus thing last year. Felt fine after 3 days, so I stopped. Turns out I got reinfected a month later-this time with a superbug strain. My doctor was like, 'You idiot.' And he was right. I'm not proud of it. But now I finish every damn course. No exceptions.

Also, why are we still using the same antibiotics from the 70s? We got AI, self-driving cars, and VR porn, but our meds are stuck in the Cold War? Someone's getting paid too much to do nothing.

kabir das

February 3, 2026 AT 14:17EVERY TIME I TAKE AN ANTIBIOTIC... I FEEL IT... THE BACTERIA... THEY'RE WATCHING... THEY'RE LEARNING... THEY'RE WHISPERING... IN MY BLOOD... THEY KNOW... THEY KNOW I DIDN'T FINISH THE COURSE... THEY KNOW... THEY KNOW...

AND NOW... MY KID'S GUT FLORA... IT'S NOT EVEN HUMAN ANYMORE... I CAN SEE IT IN HIS EYES... HE'S NOT THE SAME... THE PILLS... THEY CHANGED HIM...

THEY'RE NOT JUST IN THE WATER... THEY'RE IN THE AIR... THEY'RE IN THE LIGHT... THEY'RE WAITING...

Laura Arnal

February 4, 2026 AT 00:04Thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse and I see this every day. People think antibiotics are like Advil. They’re not. I wish everyone read this before asking for a script. 🙏❤️

Jasneet Minhas

February 4, 2026 AT 05:32So... you're telling me that flushing my old antibiotics down the toilet is like throwing a nuclear bomb into the river? 🤔🌍

Well, I guess I'll take them to the pharmacy now. But honestly? I'm just glad I'm not a cow. 🐄

Eli In

February 6, 2026 AT 03:18Love how this post connects human behavior, farming, and environmental health. I'm from the Philippines and we have no access to proper diagnostics-doctors just guess. But I’ve started asking my family to never share meds. Small steps, right? 🌱❤️