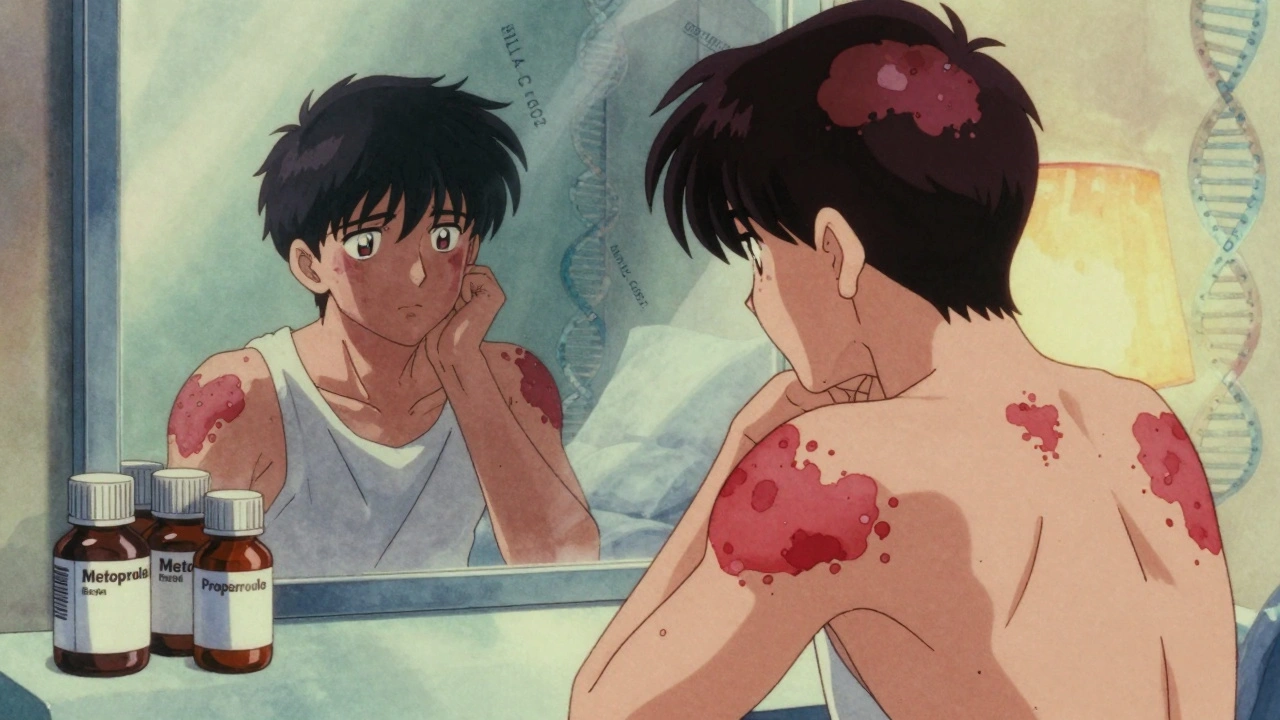

When your skin breaks out in thick, red, scaly patches, it’s easy to think it’s just a cosmetic issue. But if those patches come with stiff, swollen fingers, achy heels, or lower back pain, you’re not just dealing with a skin condition-you’re facing something deeper. Psoriatic arthritis is the hidden partner of psoriasis, an autoimmune disease that attacks not just your skin, but your joints, tendons, and even your heart. And most people don’t realize it’s happening until the damage is already there.

What Exactly Is Psoriatic Arthritis?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) isn’t just arthritis that happens to someone with psoriasis. It’s a full-body autoimmune condition where your immune system turns on healthy tissue. In psoriasis, it targets skin cells, causing them to multiply too fast and form plaques. In PsA, it attacks the joints, the places where tendons and ligaments connect to bone, and even the nails. About 30% of people with psoriasis will develop PsA, according to the American College of Rheumatology’s 2022 guidelines. For most, the skin comes first-about 85% of cases show psoriasis years before joint symptoms. But in 5 to 10% of cases, the joints hurt before the skin ever breaks out. That’s why doctors now look for joint pain in anyone with psoriasis, no matter how mild.How Does It Show Up?

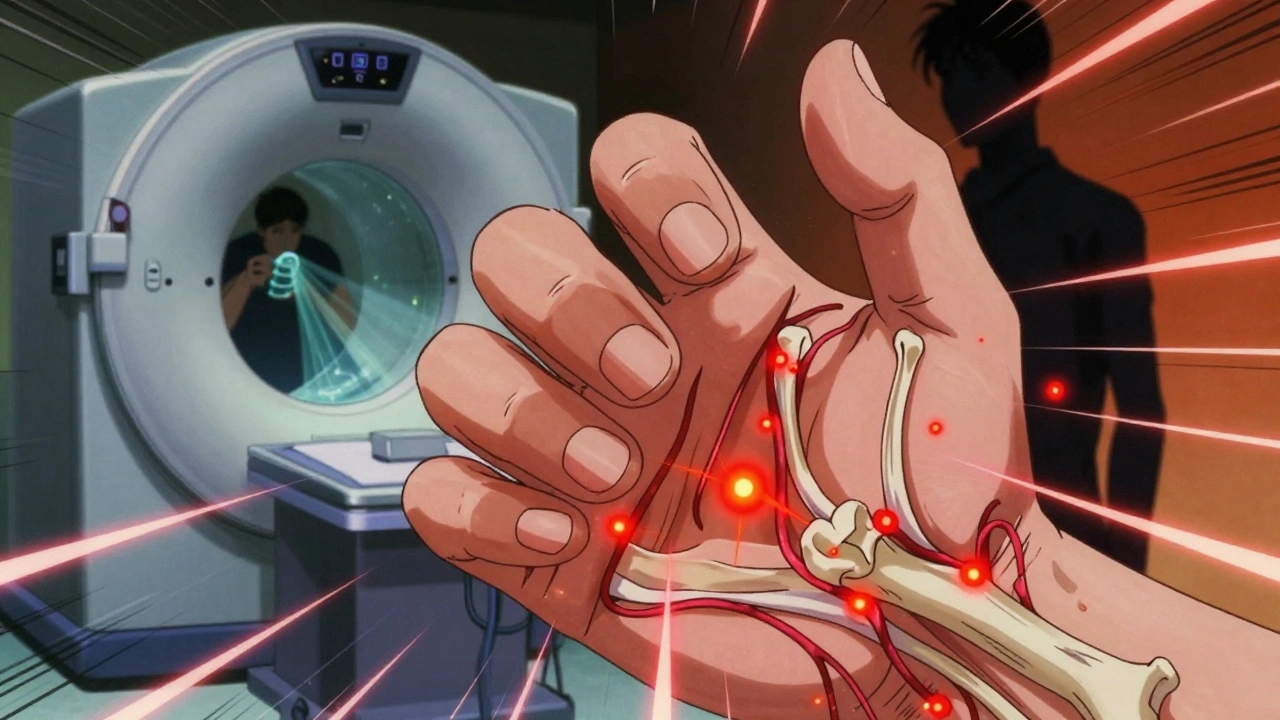

PsA doesn’t look like regular arthritis. It’s messy. It doesn’t follow patterns. One person might have swollen fingers that look like sausages-this is called dactylitis-and it happens in nearly 4 out of 10 PsA patients. Another might feel pain at the bottom of their foot where the Achilles tendon attaches to the heel. That’s enthesitis, and it affects 35 to 50% of people with PsA. Some get lower back pain that feels like sciatica but doesn’t improve with rest. Others notice their nails pitting, thickening, or pulling away from the nail bed-this happens in about 80% of cases. The skin plaques themselves are classic: raised, red, covered in silvery scales. But here’s the thing-your skin doesn’t have to be severe for PsA to be serious. Even people with just a few patches can have aggressive joint damage. That’s why doctors don’t judge PsA by how much skin is affected. They look at what’s happening inside.How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no single blood test for PsA. No magic marker. Diagnosis relies on connecting the dots. The gold standard is the CASPAR criteria, developed in 2006 and still used today. To get a confirmed diagnosis, you need inflammatory joint disease plus at least three of these:- Current or past psoriasis (3 points)

- Psoriatic nail changes like pitting (1 point)

- Negative rheumatoid factor (1 point-this helps rule out rheumatoid arthritis)

- Dactylitis (1 point)

- Characteristic bone changes on X-ray, like pencil-in-cup deformities (1 point)

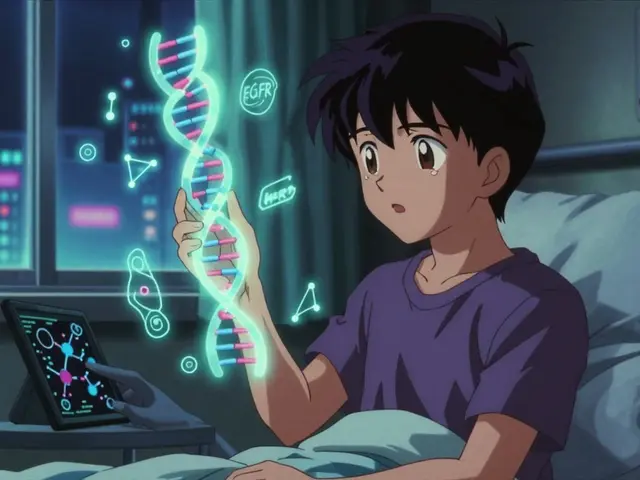

What’s Happening Inside Your Body?

Your immune system is supposed to protect you. In PsA, it’s gone rogue. Genetic factors play a big role. People with certain HLA genes-like HLA-B27, HLA-B38, and HLA-B39-are far more likely to develop it. But genes alone don’t cause it. Something triggers it. That could be stress, an infection, injury, or even changes in your gut bacteria. Recent research shows PsA patients have different gut microbes than people without it. This gut-skin-joint connection is now a major focus of study. The inflammation isn’t random. It’s driven by specific proteins-especially TNF-alpha, IL-17, and IL-23. These are like alarm bells in your immune system, telling cells to attack. That’s why modern treatments target them directly. Blocking TNF-alpha, for example, reduces joint swelling and skin plaques in about half of patients. Blocking IL-17 works even better for skin symptoms. And new drugs like deucravacitinib, which targets TYK2, are showing promise for people who don’t respond to older options.Treatment: It’s Not One-Size-Fits-All

Treatment starts with what’s manageable. For mild joint pain, over-the-counter NSAIDs like ibuprofen can help. But they don’t stop the disease. If symptoms persist, doctors move to DMARDs like methotrexate-taken weekly, it slows joint damage in many patients. But for moderate to severe PsA, biologics are the game-changer. These are injectable or infused drugs that block specific parts of the immune system:- TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept): Best for back pain and enthesitis

- IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab, ixekizumab): Top choice if skin plaques are the main problem

- IL-12/23 inhibitors (ustekinumab): Good for both skin and joints

- JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib): Oral pills, useful when injections aren’t preferred

May .

December 3, 2025 AT 12:23My skin flares and my knees ache but I just thought I was getting old. Guess I’m not.

Michael Bene

December 4, 2025 AT 11:22Oh wow, so psoriasis isn’t just ‘bad skin’-it’s your immune system throwing a full-on rave in your joints, tendons, and maybe even your heart? That’s wild. I mean, we’re talking about a silent assassin wearing a flaky coat. And people treat it like a zit you can scrub off? No wonder so many end up with busted knees and heart issues. The fact that 30% of psoriasis patients get PsA and most don’t know it until it’s too late? That’s not negligence-it’s a systemic failure of medicine to take the body as a whole. They treat skin like a billboard and joints like a footnote. Time to upgrade the damn operating system.

dylan dowsett

December 4, 2025 AT 14:16Wait-so you’re saying that if you have psoriasis, you should automatically assume you have psoriatic arthritis? That’s irresponsible. Not everyone with a little red patch on their elbow has dactylitis. You’re scaring people. And what about the people who have joint pain but no psoriasis? Are they just… invisible? This article reads like a pharmaceutical ad disguised as medical advice. You’re over-diagnosing, over-treating, and over-fearing. Stop it.

Chad Kennedy

December 4, 2025 AT 19:36I’ve had psoriasis for 15 years. My fingers hurt every morning. I thought it was just arthritis from typing too much. Turns out? It’s this. I cried. I’m not even mad. Just… tired. Why didn’t anyone tell me this was connected? I’ve been suffering alone for a decade.

Cyndy Gregoria

December 6, 2025 AT 09:15You’re not alone. If you’re reading this and feeling scared-take a breath. You’re not broken. You’re not failing. You just need the right team. Find a rheumatologist who listens. Track your symptoms. Ask for the blood tests. Ask for the scans. You deserve to feel better. This isn’t just about skin or joints-it’s about your life. And you’re worth fighting for.

Mark Gallagher

December 7, 2025 AT 08:01According to the CASPAR criteria, you need three points. But this article ignores the fact that many patients are misdiagnosed with RA because doctors don't know the difference. And the U.S. healthcare system doesn't prioritize early screening. This isn't science-it's profit-driven reactive care. If you're not wealthy, you're not getting screened until you're crippled. That's not a medical issue. That's a moral failure.

Wendy Chiridza

December 9, 2025 AT 07:04I was diagnosed with PsA last year after my nails started lifting and my heel hurt for months. My dermatologist didn’t mention it. My primary care said it was plantar fasciitis. I had to push for a rheumatologist. The article is right-doctors are too focused on skin. But it’s not their fault. They’re overwhelmed. We need better training. And more time.

Pamela Mae Ibabao

December 9, 2025 AT 19:02So you’re telling me my ‘ugly skin’ is actually a sign my body is trying to kill me? And the fact that I’m depressed isn’t just ‘in my head’-it’s inflammation? That’s terrifying. But also… kind of makes sense. I’ve been on biologics for a year. My skin cleared. My joints don’t creak anymore. But I still feel like a ghost. Is that normal? Or am I just broken now?

Gerald Nauschnegg

December 10, 2025 AT 00:17Hey, I’ve got PsA and I’m a personal trainer. I lift weights. I run. I eat clean. I’m not letting this win. If you’re reading this and you think you’re too tired or too sore to move-try walking 10 minutes a day. Movement is medicine. I know it sounds cliché. But it’s true. Your joints need to move. Don’t wait for a pill to fix you. Move. Breathe. Fight.

Palanivelu Sivanathan

December 10, 2025 AT 23:17Life is a paradox, my friends. The skin that shields us becomes the battlefield. The joints that carry us become the prison. And the immune system-the very thing meant to protect us-becomes the traitor. Is this not the ultimate irony? We are both the temple and the vandal. The healer and the destroyer. Perhaps PsA is not a disease… but a cosmic whisper. A reminder that we are not separate from our bodies. We are our bodies. And when one part screams, the whole soul must listen.

Joanne Rencher

December 12, 2025 AT 17:31Ugh. Another ‘you’re not just sick, you’re a whole system’ article. Newsflash: I don’t care. I just want my knees to stop hurting. Stop preaching. Just give me a pill that works.

Erik van Hees

December 14, 2025 AT 16:10Guys, I’ve been on three different biologics. I’ve had MRIs, blood draws, and a biopsy. I’ve seen the numbers. The data is solid. This isn’t hype. This is real. And the new IL-23 drugs? They’re a game-changer. If you’re on methotrexate and still hurting-you’re not failing. Your treatment just isn’t advanced enough yet. Ask for a referral. Push. Don’t settle. You’ve got this.

Cristy Magdalena

December 15, 2025 AT 04:00I didn’t realize how much I hated my body until I saw the pitting in my nails. I stopped wearing sandals. I stopped looking in the mirror. I stopped talking to people. I thought I was just being dramatic. But now I know-it’s not me. It’s the disease. And I’m so tired of being told to ‘just be positive.’ Sometimes, being tired is enough. And that’s okay.