Diabetes Medication Decision Guide

This tool helps identify which diabetes medications might be most appropriate for your situation based on the latest clinical guidelines. It's designed to inform discussions with your healthcare provider, not replace medical advice.

Your Health Profile

This tool is for informational purposes only and should not be used to make medical decisions. Always consult with your healthcare provider before changing any medications.

Key Takeaways

- Metformin remains the first‑line choice for most people with type‑2 diabetes because it’s cheap, weight‑neutral and has proven cardiovascular benefits.

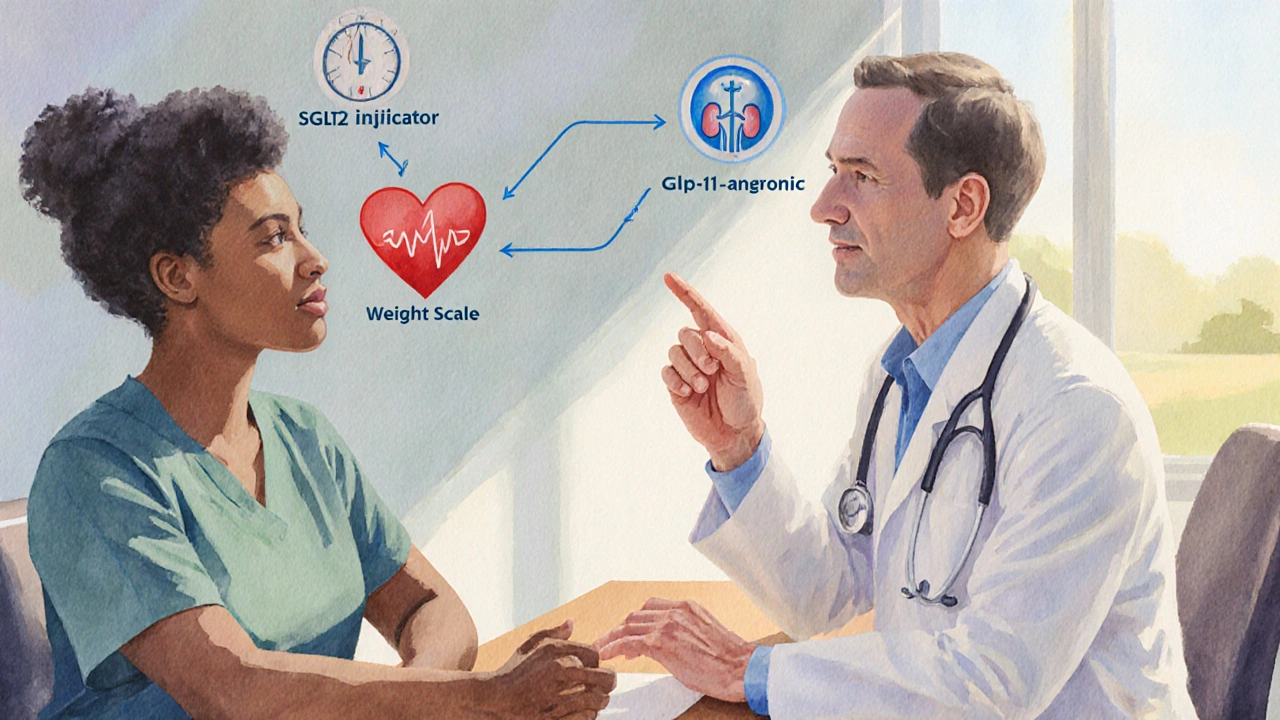

- Newer classes-SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP‑1 agonists-show stronger heart‑ and kidney‑protective effects but cost more and may cause gastrointestinal or genitourinary side effects.

- Sulfonylureas are inexpensive and fast‑acting but raise hypoglycemia risk and often lead to weight gain.

- DPP‑4 inhibitors are safe and weight‑neutral but provide only modest glucose lowering.

- Choosing the right alternative depends on your A1C target, existing heart/kidney disease, budget and tolerance for side effects.

When you or a loved one is diagnosed with type‑2 diabetes, the first medication you’ll hear about is usually Glucophage, the brand name for Metformin is a big‑uanide that reduces liver glucose output and improves insulin sensitivity in muscle. While Metformin works well for many, doctors often consider other drug families when the response isn’t enough, side effects appear, or specific health conditions demand extra protection. This guide walks you through the most common alternatives, compares them on key dimensions, and helps you decide which option fits your health goals.

How Metformin (Glucophage) Works

Metformin targets two primary pathways:

- It suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis, meaning the liver makes less glucose.

- It enhances peripheral glucose uptake by increasing insulin sensitivity in muscle cells.

Because it doesn’t stimulate insulin secretion, the risk of hypoglycemia is low. It also modestly helps with weight loss or weight maintenance, which is a bonus for many patients. The drug has been on the market since the late 1950s and is supported by decades of outcome data showing reduced cardiovascular events.

Common Alternatives to Metformin

Below are the major drug classes that doctors prescribe when Metformin alone isn’t enough or when patients can’t tolerate it.

- Sulfonylureas are a class of medications that increase insulin release from the pancreas. A typical example is Glipizide, which works quickly to lower blood sugar but can cause weight gain and a higher chance of hypoglycemia.

- DPP‑4 inhibitors block the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase‑4, prolonging the action of incretin hormones that stimulate insulin after meals. Sitagliptin is a well‑known drug in this group; it’s weight‑neutral and carries a low hypoglycemia risk.

- SGLT2 inhibitors prevent the kidneys from re‑absorbing glucose, causing excess sugar to be flushed in the urine. Empagliflozin not only lowers A1C but also reduces heart‑failure hospitalization and slows chronic kidney disease progression.

- GLP‑1 receptor agonists mimic the incretin hormone glucagon‑like peptide‑1, boosting insulin secretion, slowing gastric emptying, and promoting satiety. Liraglutide can produce significant weight loss and offers strong cardiovascular protection.

- Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) activate the PPAR‑γ receptor to improve insulin sensitivity in fat and muscle. Pioglitazone is the most widely used TZD, but it may cause fluid retention and increase fracture risk.

Comparison Criteria

To see how each alternative stacks up, we’ll evaluate them on six practical dimensions that matter to patients and clinicians.

- Glycemic efficacy - average reduction in A1C.

- Impact on body weight.

- Risk of hypoglycemia.

- Cardiovascular and renal outcomes.

- Common side‑effects.

- Typical out‑of‑pocket cost in the United States (2025 pricing).

Side‑by‑Side Comparison Table

| Drug Class | A1C ↓ (average %) | Weight Effect | Hypoglycemia Risk | Cardio‑Renal Benefit | Common Side‑Effects | Typical Monthly Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metformin (Glucophage) | 0.8-1.5 | ‑0.5 to ‑2kg | Low | Reduced MI & stroke; modest kidney protection | GI upset, metallic taste | $4-$10 |

| Sulfonylureas (e.g., Glipizide) | 0.8-1.3 | +1 to +3kg | High | Neutral | Hypoglycemia, weight gain | $5-$15 |

| DPP‑4 inhibitors (e.g., Sitagliptin) | 0.5-0.8 | Neutral | Low | Neutral | Nasopharyngitis, mild GI | $100-$150 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors (e.g., Empagliflozin) | 0.6-1.0 | ‑1 to ‑3kg | Low | ↓ HF hospitalization, ↓ CKD progression | UTIs, genital mycotic infections, dehydration | $150-$250 |

| GLP‑1 agonists (e.g., Liraglutide) | 0.8-1.4 | ‑3 to ‑6kg | Low | ↓ ASCVD events, weight loss benefits | Nausea, vomiting, pancreatitis (rare) | $300-$400 |

| Thiazolidinediones (e.g., Pioglitazone) | 0.5-1.0 | Neutral to +2kg | Low | Improved insulin sensitivity; neutral cardio | Edema, weight gain, fracture risk | $30-$60 |

*Costs are average wholesale prices for a typical adult dose in 2025 and may vary by insurance.

When Metformin Is Still the Best Choice

If you’re looking for a low‑cost, well‑tolerated option with proven heart benefits, Metformin stays first‑line for most patients without severe kidney disease (eGFR≥45mL/min). It works well in combination with almost any other class, so doctors often keep it even after adding a second agent.

When to Consider an Alternative First

Some situations push clinicians toward other drugs right away:

- Established cardiovascular disease or heart‑failure: SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP‑1 agonists have the strongest data for reducing major adverse cardiac events.

- Chronic kidney disease (eGFR<45mL/min): Certain SGLT2 inhibitors remain effective and protect kidneys even at lower eGFR, whereas Metformin dose must be reduced or stopped.

- Obesity: GLP‑1 agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors help with weight loss, while sulfonylureas may worsen it.

- History of severe GI intolerance to Metformin: DPP‑4 inhibitors or low‑dose sulfonylureas may be easier on the stomach.

Practical Tips & Common Pitfalls

Regardless of which drug you end up on, keep these habits in mind:

- Take Metformin with meals to reduce GI upset.

- Monitor kidney function at least annually; adjust dose if eGFR drops.

- If you start an SGLT2 inhibitor, stay hydrated and watch for signs of urinary infection.

- Never skip meals while on sulfonylureas; low carbohydrate intake spikes hypoglycemia risk.

- For injectable GLP‑1 agonists, rotate injection sites and keep the pen refrigerated.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I take Metformin and an SGLT2 inhibitor together?

Yes. The combination is common because Metformin tackles liver glucose production while SGLT2 inhibitors increase urinary glucose excretion, giving an additive A1C drop without a higher hypoglycemia risk.

Why does Metformin cause a metallic taste?

The metal‑like sensation comes from Metformin’s effect on the gastrointestinal lining; it’s harmless and usually fades after a few weeks or with a gradual dose increase.

Are GLP‑1 agonists safe for people without diabetes?

Some GLP‑1 drugs have FDA approval for obesity management in non‑diabetic patients, but they must be prescribed by a specialist and monitored for nausea and rare pancreatitis.

What should I do if I experience a urinary tract infection while on an SGLT2 inhibitor?

Stop the SGLT2 inhibitor temporarily, increase fluid intake, and see your doctor for antibiotics. After the infection clears, the medication can usually be restarted.

Is it okay to switch from a sulfonylurea to Metformin if I gain weight?

Absolutely. Metformin typically helps with modest weight loss, and the transition can be done gradually to avoid blood‑sugar spikes.

Do DPP‑4 inhibitors affect blood pressure?

They have a neutral effect on blood pressure, making them a safe addition if you already take antihypertensive meds.

How often should I have my A1C checked after starting a new diabetes drug?

A baseline test, then repeat in 3 months to gauge effectiveness. If the target isn’t met, your doctor may adjust dosage or add another agent.

Next Steps & Troubleshooting

If you’re already on Metformin and it’s not enough, schedule an appointment to discuss adding or switching to one of the alternatives listed above. Bring recent lab results (A1C, kidney function, lipid panel) so the clinician can match the drug’s strengths to your health profile. Should you experience side‑effects, don’t stop the medication abruptly-contact your provider for dose adjustments or a possible switch.

Remember, diabetes management isn’t just about pills. Pair any drug regimen with a balanced diet, regular activity, and routine monitoring for the best outcomes.

Metformin remains the cornerstone, but the expanding toolbox means you can tailor therapy to your unique needs.

Adam Craddock

October 12, 2025 AT 02:21The article presents a comprehensive overview of metformin versus newer agents, yet I wonder how the cardiovascular outcome data compare across different patient subgroups, particularly those with established heart failure.

Kimberly Dierkhising

October 12, 2025 AT 13:27Your observation about subgroup analysis is spot‑on; when we stratify patients by ejection fraction, SGLT2 inhibitors consistently demonstrate a 20‑30% relative risk reduction in hospitalization for heart failure, which is not mirrored to the same extent by DPP‑4 inhibitors.

Moreover, the pharmacodynamic profile of empagliflozin, involving natriuresis and improved myocardial energetics, underpins these benefits.

Clinicians should therefore weigh these mechanistic nuances when personalizing therapy.

Rich Martin

October 13, 2025 AT 00:34Metformin may be old school, but it still kicks ass for most Type‑2 diabetics.

The newer GLP‑1 drugs are flashy, yet their price tags are absurd.

If you can't afford them, why the hell are doctors pushing them like miracle cures?

The data shows SGLT2 inhibitors protect kidneys, but they also cause UTIs that can be a nightmare.

Sulfonylureas are cheap, but they crash your blood sugar like a roller coaster.

The real question is: are we treating patients or our pharma sponsors?

Honestly, the guidelines feel like a marketing brochure.

Bottom line – pick the drug that fits the patient's wallet and health profile, not the latest hype.

Buddy Sloan

October 13, 2025 AT 11:41I hear you, Rich – the cost factor is huge for many folks 😊.

Balancing efficacy with affordability is a real challenge, especially when insurance coverage varies.

It's great that metformin remains a solid first‑line option for those who need it without breaking the bank.

SHIVA DALAI

October 13, 2025 AT 22:47The sheer cost disparity between metformin and GLP‑1 agonists is nothing short of a public health crisis.

Vikas Kale

October 14, 2025 AT 09:54Indeed, the pricing chasm reflects deeper systemic issues. 📊

While GLP‑1 agonists boast superior weight‑loss outcomes and cardiovascular risk reduction – evidenced by the LEADER trial – their wholesale acquisition cost eclipses metformin by an order of magnitude.

From a pharmacoeconomic standpoint, payers often resort to step‑therapy protocols, mandating metformin trial before escalation, which can delay optimal therapy for high‑risk patients.

Moreover, biosimilar pipelines may eventually attenuate these gaps, but until then clinicians must navigate the trade‑off between clinical benefit and fiscal feasibility.

Deidra Moran

October 14, 2025 AT 21:01The so‑called "evidence‑based" recommendations are nothing more than a veil for pharmaceutical lobbying.

Don't be fooled by the glossy charts; they're engineered to steer patients toward profit‑driven therapies.

Zuber Zuberkhan

October 15, 2025 AT 08:07While skepticism is healthy, we also have to acknowledge the robust trial data supporting SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP‑1 agonists, especially for cardiovascular protection.

Let's aim for a balanced view that respects both scientific rigor and patient access.

Tara Newen

October 15, 2025 AT 19:14Metformin's cost-effectiveness is undeniable, yet the newer agents bring undeniable clinical advantages that can't be ignored.

It's a matter of prioritizing health outcomes over short-term savings.

Amanda Devik

October 16, 2025 AT 06:21Totally agree Tara – health matters more than pennies

Patients deserve the best evidence‑based care even if it costs a bit more

Mr. Zadé Moore

October 16, 2025 AT 17:27Guidelines masquerade as neutral while they push high‑margin drugs.

Brooke Bevins

October 17, 2025 AT 04:34That's a sharp observation, Mr. Moore 😠.

Transparency in guideline development is crucial to maintain trust.

Vandita Shukla

October 17, 2025 AT 15:41The article glosses over patient adherence issues linked to side‑effects like GI upset from metformin.

Susan Hayes

October 18, 2025 AT 02:47Adherence is indeed a silent killer in diabetes management; side‑effect profiles must be weighed against efficacy.

Jessica Forsen

October 18, 2025 AT 13:54Oh great, another table that tells us what we already know – cheaper drugs work, expensive ones work better, pick your poison.

Deepak Bhatia

October 19, 2025 AT 01:01It can be confusing, but talking with a doctor can help sort out what works best for you.

Samantha Gavrin

October 19, 2025 AT 12:07Don't trust the pharma‑backed data; they're hiding long‑term risks of GLP‑1 drugs that aren't published in mainstream journals.

NIck Brown

October 19, 2025 AT 23:14While vigilance is needed, the peer‑reviewed studies consistently show cardiovascular benefits, making it hard to dismiss outright.

Andy McCullough

October 20, 2025 AT 10:21When evaluating diabetes pharmacotherapy, it's essential to move beyond a simplistic cost‑versus‑efficacy dichotomy and consider the nuanced interplay of metabolic pathways, patient comorbidities, and long‑term outcome data.

Metformin's mechanism of reducing hepatic gluconeogenesis and enhancing peripheral insulin sensitivity has withstood decades of scrutiny, delivering modest A1C reductions while maintaining a low hypoglycemia risk.

However, in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, the EMPA‑REG OUTCOME and LEADER trials have demonstrated that SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP‑1 agonists, respectively, confer a statistically significant reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events.

These benefits are not merely statistical artifacts; they translate into real‑world reductions in myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart‑failure hospitalizations, which are critical endpoints for a population already burdened by polypharmacy.

From a renal perspective, the CREDENCE and DAPA‑CKD studies provide compelling evidence that SGLT2 inhibition can slow the progression of chronic kidney disease, an advantage that metformin cannot reliably claim, especially in patients with eGFR below 45 mL/min.

Weight management is another differentiator: GLP‑1 receptor agonists consistently produce 5–10 % body‑weight reductions, a therapeutic effect that can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce cardiovascular strain.

Conversely, sulfonylureas, while inexpensive, are associated with weight gain and a markedly higher incidence of severe hypoglycemia, which can be particularly hazardous in older adults.

DPP‑4 inhibitors sit in a middle ground, offering weight neutrality and low hypoglycemia risk, yet their modest A1C lowering effect (≈0.5–0.8 %) may be insufficient for patients with markedly elevated baseline glucose.

Economic considerations cannot be ignored: generic metformin costs as little as $4–$10 per month, whereas branded GLP‑1 agents can exceed $400, a disparity that influences insurance formularies and out‑of‑pocket expenses.

Nevertheless, many health systems are adopting value‑based contracts that offset the upfront cost of cardioprotective agents by accounting for downstream savings from avoided hospitalizations.

Clinicians should therefore adopt a tiered algorithm: initiate metformin in drug‑naïve patients without contraindications, assess A1C response, and then layer on an adjunct based on individual risk factors such as heart failure, CKD, or obesity.

Patient education plays a pivotal role; understanding the potential side‑effects-genital infections with SGLT2 inhibitors, gastrointestinal upset with metformin, or nausea with GLP‑1 agonists-empowers shared decision‑making.

Moreover, adherence hinges on dosing convenience; once‑weekly GLP‑1 formulations may improve compliance compared to daily injections, while fixed‑dose combination pills reduce pill burden.

Ultimately, the decision matrix is a convergence of clinical evidence, patient preference, and socioeconomic context, requiring a personalized approach rather than a one‑size‑fits‑all prescription.

In summary, metformin remains a cornerstone, but the therapeutic landscape has expanded to include agents that address cardiovascular and renal outcomes, offering clinicians a richer toolkit to tailor therapy to each individual's profile.

Zackery Brinkley

October 20, 2025 AT 21:27Great summary, Andy – a clear guide for anyone navigating diabetes treatment options.