When you switch to a generic drug, you expect the same results as the brand-name version. But what if your body doesn’t respond the same way - not because the medicine is different, but because of your genes? For many people, the real reason a generic drug doesn’t work - or causes side effects - isn’t about cost or quality. It’s about genetics.

Why Your Genes Matter More Than You Think

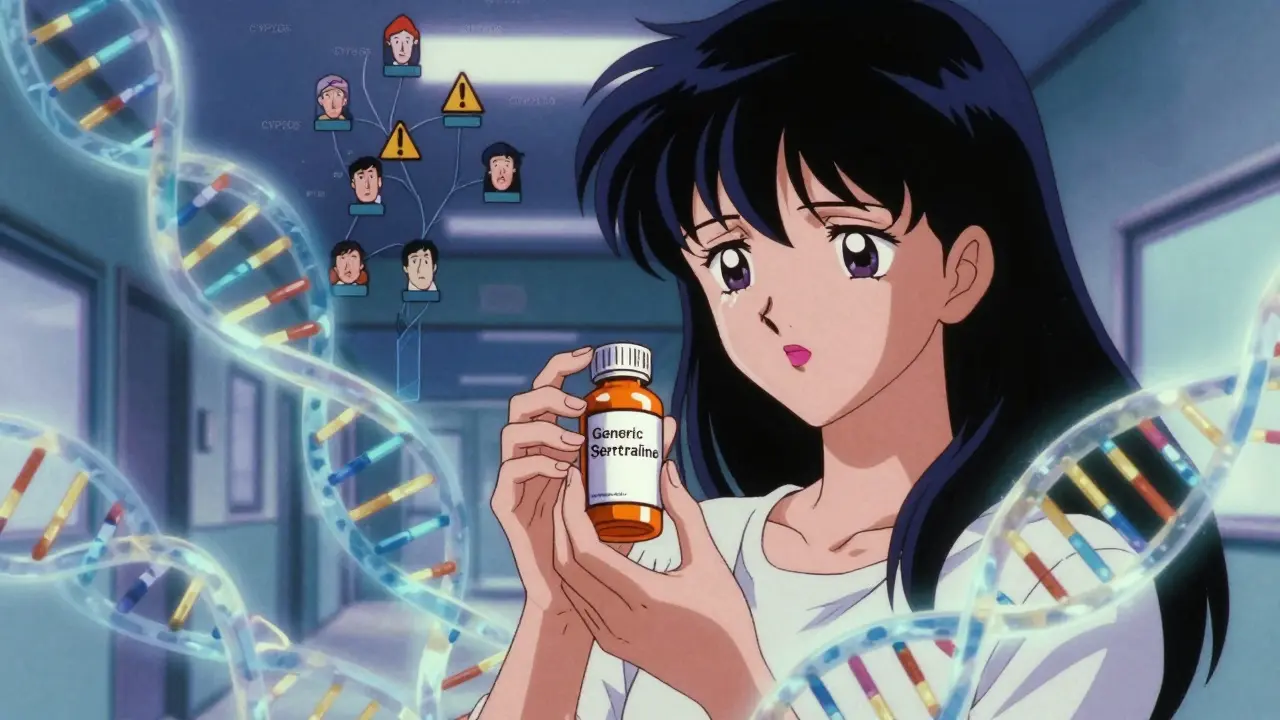

Generic drugs are required by law to have the same active ingredient as brand-name drugs. But your body doesn’t care about the label. It cares about how fast or slow it breaks down that ingredient. And that’s controlled by your genes. Take CYP2D6, one of the most important genes in drug metabolism. It handles about 25% of all prescription medications, including common antidepressants like sertraline and painkillers like codeine. If you have a variant that makes this enzyme work too slowly, you might build up dangerous levels of the drug. If it works too fast, the drug might not work at all. These differences aren’t rare. About 1 in 10 people of European descent are poor metabolizers of CYP2D6. In some Asian populations, that number jumps to 1 in 5. This isn’t theoretical. A 2023 Mayo Clinic study tracked 10,000 patients who got preemptive genetic testing. Over 40% had at least one high-risk gene-drug interaction. In two-thirds of those cases, doctors changed the medication or dose - and adverse events dropped by 34%. That’s not a small win. That’s life-changing.Family History Is a Clue, Not a Guarantee

If your parent had a bad reaction to a generic version of a blood thinner, or needed a much higher dose of an antidepressant, that’s not just bad luck. It’s a red flag. Genetics run in families. If your mother had severe side effects from warfarin, you might carry the same CYP2C9 or VKORC1 variants that make her body process it differently. Warfarin is one of the clearest examples. The FDA added genetic guidance to its label back in 2008. People with certain variants need up to 30% less of the drug. African Americans, on average, need higher doses than Europeans because of different genetic patterns in those same genes. But guessing based on race or family history alone isn’t enough. That’s why doctors are moving toward testing. One patient on Reddit shared that after her Color Health test showed a DPYD gene variant, her oncologist cut her 5-FU chemotherapy dose in half. She finished treatment without the life-threatening nausea and low blood counts others in her group suffered. Her family had no history of chemo reactions - but her genes did.

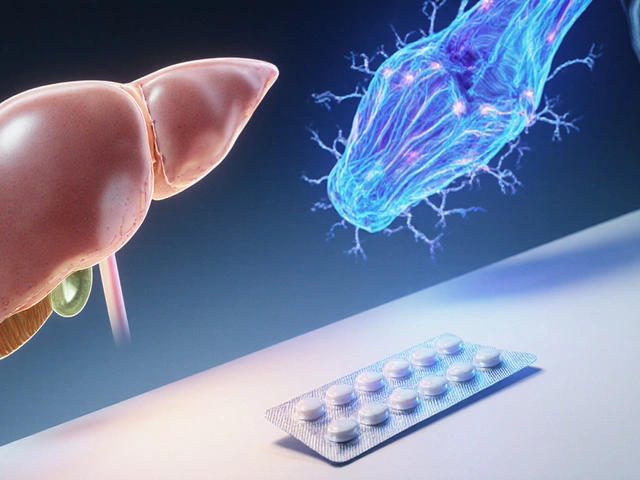

Why Generics Can Still Cause Problems

You might think: “If the active ingredient is the same, why does it matter?” Because your body doesn’t just react to the ingredient - it reacts to how fast it enters your bloodstream and how quickly it’s cleared. That’s where your liver enzymes come in. Take proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole. These are common for heartburn. But if you’re a poor metabolizer of CYP2C19 - which affects 15-20% of Asians and 2-5% of Caucasians - you might end up with too much of the drug in your system. That increases your risk of bone fractures and kidney problems over time. A generic version isn’t safer just because it’s cheaper. It’s the same drug. Same risk. Same gene interaction. The same goes for clopidogrel (Plavix). If you have a CYP2C19 loss-of-function variant, your body can’t activate the drug properly. That means it won’t prevent clots. In 2020, the FDA issued a boxed warning about this. Yet many doctors still prescribe it without testing - especially when switching to generics.Testing Is Available - But Not Always Used

You can get tested. Companies like Color Genomics and OneOme offer panels that check 10-20 key genes for under $300. Some insurance plans cover it. Medicare now pays for certain tests under its Molecular Diagnostic Services Program. Hospitals like Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt have been doing preemptive testing for years - testing patients once, then using the results for every future prescription. But here’s the catch: most primary care doctors don’t order these tests. A 2022 survey found that only 32% of clinicians felt confident interpreting results for HLA-B*15:02 and carbamazepine, even though that variant can cause deadly skin reactions. And 79% said they didn’t have time to review genetic reports. Electronic health records are slowly catching up. Epic Systems added alerts for 12 high-risk gene-drug pairs in 2022. But if your doctor doesn’t know your genetic profile, they won’t see the warning.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to wait for a crisis to act. Here’s what works:- If you’ve had unexplained side effects from a generic drug - nausea, dizziness, no effect - ask your doctor if pharmacogenetic testing could help.

- Bring up your family history. “My mom had a bad reaction to X,” or “My dad needed double the dose of Y.” That’s valuable data.

- Ask if your prescription has a known genetic interaction. Drugs like warfarin, clopidogrel, codeine, tamoxifen, and certain antidepressants have strong evidence.

- Check if your pharmacy or clinic offers free or low-cost testing. Some community health centers now partner with testing labs.

The Future Is Personal - Even for Generics

The FDA now lists over 300 drugs with pharmacogenetic information on their labels. That number keeps growing. The NIH spent $127 million on pharmacogenomics research in 2023 alone - much of it focused on underrepresented groups, because most early studies were done in white populations. We’re moving away from “one-size-fits-all” medicine. Even generics aren’t one-size-fits-all. Your genes decide whether a drug works, doesn’t work, or makes you sick. The good news? You don’t need to guess anymore. Testing is here. Guidelines exist. Doctors are learning. And the data shows it saves lives. If you’ve ever wondered why a generic didn’t work for you - or why it caused side effects others didn’t have - your genes might be the answer. It’s not about the pill. It’s about you.Can family history alone tell me how I’ll respond to generic drugs?

Family history is a strong clue - if multiple relatives had bad reactions to the same drug, it’s likely genetic. But it’s not foolproof. Some gene variants skip generations or show up unexpectedly. Genetic testing gives you a direct readout of your DNA, not an educated guess based on relatives.

Are generic drugs less safe than brand-name drugs because of genetics?

No. Generic drugs are chemically identical to brand-name versions. The difference isn’t in the pill - it’s in how your body processes it. A generic isn’t riskier. But if your genes affect how you metabolize the drug, you’re at risk whether it’s generic or brand-name.

Which drugs are most affected by genetic differences?

The top drugs with proven genetic links include warfarin (blood thinner), clopidogrel (antiplatelet), codeine (painkiller), tamoxifen (breast cancer), and several antidepressants like sertraline and paroxetine. Chemotherapy drugs like 5-fluorouracil and thiopurines (used for leukemia and autoimmune diseases) also have strong genetic guidelines. Over 300 drugs now include pharmacogenetic info in their FDA labels.

Is pharmacogenetic testing covered by insurance?

It depends. Medicare covers certain tests under its Molecular Diagnostic Services Program. Some private insurers cover testing for high-risk drugs like warfarin or chemotherapy. Out-of-pocket costs range from $200 to $500. Many clinics offer sliding-scale pricing or partner with labs that provide financial aid.

What if my doctor says genetic testing isn’t necessary?

Ask for the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines. These are the gold standard for how to use genetic results in practice. If your doctor is unfamiliar, suggest they check CPIC’s website. You can also ask for a referral to a clinical pharmacist who specializes in pharmacogenomics - they’re trained to interpret these results and work with your doctor.

Can I get tested before I even start a new medication?

Yes. Hospitals like Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt do this routinely - they test patients once, then store the results in their medical records. Every time a new drug is prescribed, the system checks for interactions. This is called preemptive testing. It’s becoming more common, especially in academic centers. You can request it even if you’re not currently on medication.

Ayodeji Williams

January 7, 2026 AT 10:49Kyle King

January 9, 2026 AT 01:36Kamlesh Chauhan

January 10, 2026 AT 12:17Emma Addison Thomas

January 10, 2026 AT 16:25Mina Murray

January 11, 2026 AT 03:12Christine Joy Chicano

January 11, 2026 AT 20:05Paul Mason

January 12, 2026 AT 05:28Katrina Morris

January 13, 2026 AT 11:05steve rumsford

January 15, 2026 AT 03:46Anthony Capunong

January 17, 2026 AT 01:22Aparna karwande

January 17, 2026 AT 10:18Vince Nairn

January 17, 2026 AT 12:55Jonathan Larson

January 18, 2026 AT 17:08Alex Danner

January 18, 2026 AT 22:12Elen Pihlap

January 20, 2026 AT 20:39