Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they’re not cheap for everyone. While they cost 80-85% less than brand-name drugs on average, many people still struggle to afford them. Why? Because the U.S. doesn’t directly set prices for generics like other countries do. Instead, it relies on a patchwork of rules, rebates, and competition - and that system has big gaps.

How Medicaid Forces Drugmakers to Lower Prices

The biggest lever the government has over generic drug prices isn’t a price cap - it’s Medicaid rebates. Since 1990, drug manufacturers have been required to pay rebates to Medicaid for every generic drug sold. The formula is simple: they pay the greater of 23.1% of the average price they charge wholesalers (called the Average Manufacturer Price, or AMP), or the difference between that price and the lowest price they offer any other buyer.

In 2024, these rebates totaled $14.3 billion - 78% of all Medicaid drug rebates. That money doesn’t go to patients directly, but it keeps the overall cost of drugs lower for the program. Without this rule, manufacturers could charge much more and still sell to state Medicaid programs. It’s not perfect, but it’s the closest thing the U.S. has to a price floor for generics.

Medicare Part D and the $2,000 Cap

If you’re on Medicare, your out-of-pocket costs for generics changed dramatically in 2025. Before, you could spend thousands before hitting catastrophic coverage. Now, thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act, your maximum out-of-pocket spending for all drugs - brand or generic - is capped at $2,000 per year.

That’s huge for people taking multiple generics. A senior on lisinopril, metformin, and atorvastatin might have been paying $400-$500 a year before. Now, they pay no more than $2,000 total, no matter how many meds they need. The law also cut the deductible for Part D from $595 to $545 in 2026, and for low-income beneficiaries, many generics now cost $0 to $4.90 per prescription.

The 340B Program: Hidden Savings for the Poorest Patients

While most people think of Medicare and Medicaid when they think of drug pricing, the 340B Drug Pricing Program is quietly helping millions of low-income patients. Hospitals and clinics that serve vulnerable populations - like community health centers, free clinics, and rural hospitals - buy drugs at deeply discounted rates, often 20-50% below the average market price.

These discounts apply to both brand and generic drugs. A patient at a 340B clinic might get their generic metformin for $5 a month, while someone at a regular pharmacy pays $15. The program isn’t perfect - there’s been debate over whether some hospitals abuse it - but for those who qualify, it’s a lifeline. A 2025 survey found 87% of safety-net clinics reported better patient adherence because of lower prices.

Why Generic Prices Still Spike - and Who’s to Blame

Here’s the problem: when only one or two companies make a generic drug, prices can skyrocket. In 2024, the generic version of pyrimethamine (Daraprim) jumped 300% because only two manufacturers were left in the market. No one was competing. No one was forcing prices down.

This happens often with older, low-margin drugs - like antibiotics, thyroid meds, or seizure drugs. The FDA approves hundreds of generics every year, but many manufacturers quit making them because the profit is too thin. Some drugs have only one supplier. Others have none. When that happens, prices don’t just go up - they become unaffordable.

And it’s not just manufacturers. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) - the middlemen between insurers and pharmacies - take a cut. A Senate report in 2025 found that 68% of the so-called “savings” from generic drug rebates never reach the patient. Instead, PBMs keep them as profit. That’s why you might see a $10 copay on your screen, then get billed $45 at the counter.

How the U.S. Compares to Other Countries

Other rich countries don’t wait for competition to lower prices. They set them. In the U.K., the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) negotiates prices directly. In Germany, they evaluate whether a drug is worth its cost before allowing it on the market. Canada uses reference pricing - if a drug costs $10 in France, it can’t cost more than that in Canada.

The U.S. doesn’t do any of that. Instead, we rely on having dozens of manufacturers compete. And it works - until it doesn’t. In 2025, U.S. generic prices were 1.3 times higher than the average of 32 other OECD countries. That’s not a huge gap compared to brand-name drugs, where U.S. prices are 3-5 times higher. But for someone living on a fixed income, $15 for a generic instead of $10 still matters.

Who Wants Government to Step In - and Who Doesn’t

Some experts say the market is broken. Dr. Peter Bach from Memorial Sloan Kettering told Congress that the U.S. pays 138% more for generics than other wealthy nations. He points to the VA, which negotiates prices directly and gets 40-60% discounts. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that letting Medicare negotiate prices for a few select generics could save $12.7 billion over ten years.

But others warn it could backfire. The Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy says price controls reduce innovation. David Epstein, former CEO of Novartis, says 70% of generic makers operate on margins below 15%. If prices drop further, they’ll quit making low-profit drugs - and we’ll end up with even fewer choices.

Dr. Mark McClellan, a former FDA commissioner, suggests a middle path: fix the system so competition works better. That means cracking down on “product hopping” (when brand companies make tiny changes to delay generics), speeding up approvals, and making it harder for PBMs to hide rebates.

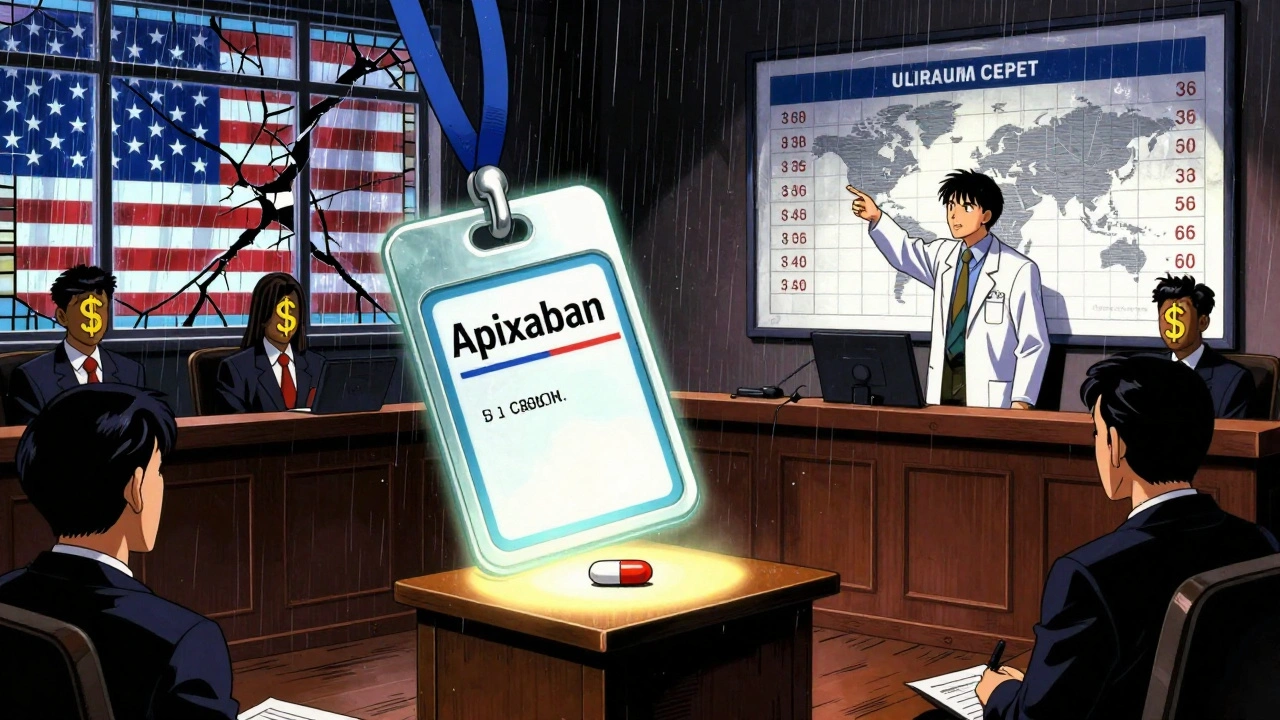

What’s Coming in 2026 and Beyond

The biggest change on the horizon isn’t about new rules - it’s about who gets targeted. Starting in 2026, Medicare will begin negotiating prices for certain high-cost drugs. But here’s the twist: the first batch includes generic versions of blockbuster drugs like apixaban (Eliquis) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto). These are generics, but they’re used by over 5 million Medicare patients and cost billions.

Industry analysts predict prices for these specific generics could drop 25-35% by 2027. That’s not a blanket price cut - it’s targeted. Only drugs with high spending and low competition will be affected. Most everyday generics - like metformin or amoxicillin - won’t be touched.

Legal challenges are already brewing. PhRMA, the drug industry lobby, sued over a proposed Most-Favored-Nation rule that would tie U.S. prices to what other countries pay. They argue it’s a government taking - and they’re not backing down.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re paying too much for generics, you’re not powerless. Here’s what works:

- Use the Medicare Plan Finder tool. Compare plans every year - formularies change, and your current plan might not be the cheapest for your meds.

- Ask your pharmacist if a different generic brand is cheaper. Sometimes two versions of the same drug cost $20 apart.

- Check if your clinic is a 340B provider. If you’re low-income, you might qualify for huge discounts.

- Use GoodRx or SingleCare. Even with insurance, these apps often show lower cash prices.

- Call your insurer. If you’re hit with a surprise $50 bill, ask why. Sometimes it’s just a PBM glitch.

The system is messy. But it’s not hopeless. You don’t need to wait for Congress to fix it. You can find the cheapest option - if you know where to look.

Why are generic drug prices so unpredictable in the U.S.?

Generic prices fluctuate because the U.S. doesn’t set them directly. Instead, prices depend on how many manufacturers are making the drug. If only one or two companies produce it, they can raise prices. If dozens are competing, prices drop. This leads to wild swings - like when pyrimethamine jumped 300% because only two makers were left. There’s no safety net for low-competition drugs.

Does Medicare negotiate generic drug prices?

Not yet for most generics. But starting in 2027, Medicare will negotiate prices for a small number of high-cost generics - like apixaban and rivaroxaban - that are used by millions of seniors. This is the first time Medicare will directly negotiate prices for generics. Most everyday generics, like metformin or lisinopril, are still priced by the market.

Can I get generic drugs for free?

Yes - if you qualify. Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) beneficiaries in Medicare Part D pay $0 to $4.90 for generics. Many 340B clinics offer generics at near-zero cost to low-income patients. Some drugmakers also have patient assistance programs. But you have to apply. It’s not automatic.

Why does my generic drug cost more this month?

Your pharmacy might have switched to a different generic manufacturer. Generic drugs are interchangeable, but each maker sets its own price. Your insurance plan may have a different copay for each version. Check your plan’s formulary or ask your pharmacist: “Is this the same drug, just a different brand?”

Do pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) make generic drugs more expensive?

Yes, indirectly. PBMs get rebates from drugmakers, but they don’t always pass those savings to you. A 2025 Senate report found 68% of generic drug rebates never reach patients. Instead, PBMs keep them as profit. That’s why your copay might say $10, but you’re charged $45 - the PBM’s hidden markup.

What’s the difference between Medicaid rebates and Medicare negotiation?

Medicaid rebates are mandatory payments drugmakers make to the government for every generic sold - they’re a tax on sales. Medicare negotiation is direct bargaining: the government says, “We’ll pay $X for this drug, or we won’t cover it.” Rebates lower the list price. Negotiation sets the final price. One is reactive. The other is proactive.

What’s Next for Generic Drug Prices?

The next five years will test whether competition alone can keep generic prices low - or if targeted government intervention is needed. The U.S. will keep approving hundreds of new generics every year, but if manufacturers keep leaving low-profit markets, shortages will return. The real question isn’t whether prices should be controlled - it’s whether we want to wait until people can’t afford their meds before we act.