Every child deserves clear vision - but many won’t get it unless someone checks. Vision problems in young kids often go unnoticed because they don’t know what normal sight should feel like. A child with one lazy eye won’t say, "I can’t see well with this eye." They’ll just squint, tilt their head, or bump into things. By the time parents notice, it might be too late to fix it fully. That’s why pediatric vision screening isn’t optional - it’s essential.

Why Screening Before Age 5 Matters

The window for fixing vision problems in children closes fast. Between birth and age 7, the brain is still learning how to use the eyes together. If one eye is blurry or misaligned, the brain starts ignoring it. That’s called amblyopia, or "lazy eye." Once a child turns 7, the brain’s ability to rewire itself drops sharply. Treatment after that age works much less often. Studies show that when amblyopia is caught before age 5, 80-95% of kids can regain normal vision with proper treatment. But if it’s missed until after age 8, success rates drop to just 10-50%. Strabismus - where eyes don’t line up - follows the same pattern. These aren’t rare issues. About 1 in 30 children have amblyopia. Nearly 1 in 40 have misaligned eyes. That’s why screening every child between ages 3 and 5 isn’t just good practice - it’s a public health must.What Gets Screened and How

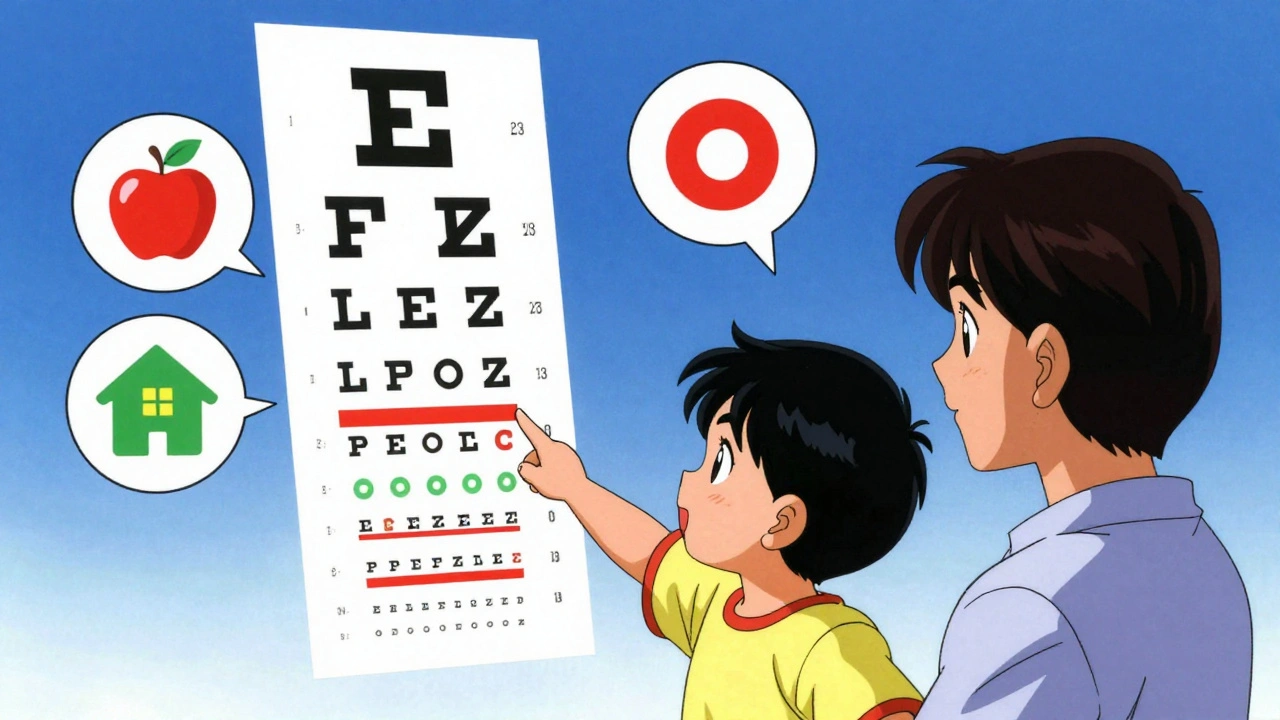

Screening isn’t one test. It’s a series of checks tailored to the child’s age and ability. For babies under 6 months, doctors check the red reflex. Using a small light tool called an ophthalmoscope, they shine light into each eye. A healthy eye reflects a bright red glow. If one eye looks dark, white, or uneven, it could mean cataracts, retinal tumors, or other serious conditions. This simple test takes seconds but can catch life-altering problems early. From 6 months to 3 years, providers look at how the eyes move, check for eyelid swelling or drooping, and watch how the child follows a toy or face. No charts yet - just observation. But around age 3, things change. Kids start to understand simple instructions. That’s when visual acuity tests begin. For 3-year-olds, they use big, colorful symbols like LEA or HOTV letters - circles, squares, apples, houses - instead of tiny E’s. They stand 10 feet away and point to matching cards. To pass, they need to get most of the symbols on the 20/50 line. By age 4, the bar rises to 20/40. At 5 and older, they aim for 20/32. If they can’t hit that mark, they’re referred for a full eye exam.Old School vs. High-Tech Screening

There are two main ways to screen: using charts and using machines. Chart-based testing is the classic method. It’s cheap, widely available, and trusted. But it needs a cooperative child. About 1 in 5 three-year-olds just won’t play along. They cry, hide, or point randomly. That’s why many clinics now use instrument-based screening - devices like the SureSight, Power Refractor, or the newer blinq™ scanner. These handheld gadgets take just 1-2 minutes. You hold them in front of the child’s face, they look at a light, and the machine reads their refractive error - whether they’re nearsighted, farsighted, or have astigmatism. The blinq™ scanner, FDA-cleared in 2018, detects referral-worthy conditions with 100% sensitivity and 91% specificity in kids aged 2-8. That means almost every child who needs help gets flagged, and few healthy kids get wrongly sent for more tests. But machines aren’t perfect. They sometimes flag kids who don’t actually need glasses - like those with small, harmless refractive errors. That can lead to unnecessary stress and visits. Chart tests, while slower, are more precise for kids who can do them. Experts agree: use machines for toddlers who won’t cooperate, and switch to charts when they’re ready.

Who Does the Screening and Where

Pediatric vision screening happens in many places: doctor’s offices, preschools, Head Start programs, and even some pharmacies. But the most consistent place is during well-child visits. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening at ages 8, 10, 12, and 15 - but the big push is for ages 3-5. Primary care providers - family doctors, pediatricians, nurse practitioners - are trained to do basic screening. Many use free online modules from the National Center for Children’s Vision and Eye Health. Training takes just 2-4 hours. After that, they’re equipped to use the right tools, measure the right distance, and interpret results correctly. One common mistake? Lighting. If the chart is too dim or too bright, results are wrong. Another? Distance. If the child stands 8 feet away instead of 10, they’ll pass when they shouldn’t. These errors happen in up to 25% of screenings. Quality checks every few months help keep things accurate.What Happens After a Positive Screen

A failed screen doesn’t mean your child needs glasses or surgery. It means they need a full eye exam by a pediatric ophthalmologist or optometrist. That’s the next step. Most insurance plans - including Medicaid - cover these exams. The Affordable Care Act requires pediatric vision services as part of essential health benefits. In 38 states, schools are legally required to screen before kindergarten. But not all screenings are equal. Some use outdated charts. Others skip the red reflex. That’s why follow-up is so important. If amblyopia is found, treatment usually means patching the good eye for a few hours a day, or using eye drops to blur it temporarily. Glasses fix many cases of refractive error. Strabismus might need glasses, vision therapy, or surgery - but only if caught early.Barriers and Inequalities

Not all kids get screened equally. Hispanic and Black children are 20-30% less likely to receive recommended vision screening, according to national health surveys. Reasons? Lack of access to pediatric care, language barriers, transportation issues, or simply not knowing it’s important. The National Eye Institute is funding $2.5 million in research to fix this gap. Some clinics now use bilingual staff, mobile screening units, and community health workers to reach underserved families. But progress is slow.What’s Next

New research shows instrument-based screening can work as early as 9 months. That could mean catching problems before a child even speaks. The American Academy of Pediatrics is expected to update its guidelines by 2025 to reflect this. If approved, screening could start at the 12-month well-baby visit. AI is also playing a bigger role. The blinq™ scanner uses machine learning to analyze images faster and more accurately than older models. More devices like this are coming. The goal? Make screening as easy as taking a temperature - quick, painless, and done at every checkup.What Parents Should Do

You don’t need to be an expert. But you do need to ask. At every well-child visit, ask: "Has my child had a vision screening?" If they’re 3 or older and haven’t had one, request it. If your child squints, sits too close to the TV, rubs their eyes constantly, or has one eye that turns in or out - don’t wait. Make an appointment. Vision screening isn’t about buying glasses. It’s about protecting a child’s future. A child with untreated amblyopia may struggle in school, avoid sports, or face lifelong challenges with depth perception. But with a 2-minute test at age 4, most of that can be avoided.Frequently Asked Questions

At what age should my child have their first vision screening?

The first formal vision screening should happen between ages 3 and 5, according to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. However, a red reflex test is done at birth and during the 6- to 9-month checkup to catch serious issues like cataracts or tumors. If your child has risk factors - like premature birth, family history of eye disease, or developmental delays - screening should start earlier and happen more often.

Can my child’s pediatrician detect vision problems?

Yes. Pediatricians are trained to perform basic vision screening using age-appropriate tools like LEA symbols, autorefractors, or red reflex tests. They’re not eye specialists, but they’re trained to spot red flags. If something looks off, they’ll refer you to a pediatric ophthalmologist for a full exam. You don’t need to go straight to an eye doctor unless your child has symptoms or a known risk factor.

Is vision screening covered by insurance?

Yes. Under the Affordable Care Act, pediatric vision screening and follow-up exams are considered essential health benefits. Most private insurance plans and Medicaid programs cover these services at no cost to families. School-based screenings are also often free. Always ask your provider about coverage - if they say it’s not covered, double-check with your insurer.

What if my child fails the screening but seems to see fine?

Many children with vision problems don’t act like they’re struggling. They adapt. One eye might be blurry, but the other sees clearly - so they compensate. That’s why screening matters. A failed screen means further testing is needed, not that your child has a major problem. Most kids who fail are found to have correctable issues like mild farsightedness or a slight eye turn. Early correction prevents long-term damage.

Are there signs I should watch for at home?

Yes. Watch for frequent eye rubbing, squinting, tilting the head, closing one eye to see, sitting too close to screens, or trouble with depth perception (like missing the ball during catch). Also, if one eye looks different - crossed, droopy, or cloudy - get it checked right away. These aren’t always obvious, but they’re warning signs.

Linda Migdal

December 1, 2025 AT 20:59Let me be clear: if we're not mandating vision screening at every pediatric visit like we do with vaccines, we're failing our kids. The data is irrefutable - 80-95% success rate before age 5? That’s not a suggestion, it’s a moral imperative. We screen for lead poisoning, we screen for autism, why is this still optional? This isn’t about glasses - it’s about neuroplasticity, cortical development, and national productivity. Stop treating eye health like a luxury.

And stop letting schools do half-assed screenings with outdated charts. If you’re not using instrument-based tech like blinq™, you’re doing harm by false reassurance. The AMA, AAP, and AAO all agree - it’s time to codify this into federal protocol. No more excuses.

Tommy Walton

December 2, 2025 AT 03:46👁️🗨️ The brain rewires itself like a neural startup - until age 7, it’s still in MVP mode. Miss the window? You’re stuck with legacy code. No patching. No updates. Just a slow, silent system crash.

Also, why are we still using charts? We have AI that can detect refractive error faster than a toddler can cry. If your pediatrician is still squinting at LEA symbols like it’s 1998, fire them. 🚨

James Steele

December 3, 2025 AT 00:13There’s a profound epistemological crisis here - we’ve outsourced the responsibility of sensory development to overworked pediatricians who’ve been trained via 3-hour online modules while juggling 30 patients an hour. The very architecture of our healthcare system is structurally incapable of detecting amblyopia in a timely manner.

Instrument-based screening isn’t just a tool - it’s a paradigm shift. The blinq™ scanner doesn’t just measure refraction - it measures the silence between a child’s potential and their reality. We’re not screening eyes. We’re auditing the integrity of a child’s future. And yet, we treat it like a checkbox. How tragic. How profoundly bourgeois.

Louise Girvan

December 3, 2025 AT 12:56They’re lying. Every single one. The AAP? The FDA? The ‘studies’? All funded by Big Optometry. You think they want kids to see better? No - they want you buying $600 glasses every year. The ‘success rate’? Fabricated. Patching doesn’t fix anything - it just makes kids miserable. And those ‘referral-worthy’ flags? Most kids are fine. They’re just being kids. Stop panicking. Stop overtesting. Let nature take its course. 🤫

soorya Raju

December 4, 2025 AT 06:38bro i think this whole thing is a scam. why do u need screening at 3? my cousin in delhi saw fine till 10, now he’s a engineer. u think america needs all this tech? we dont even have clean water but u want to buy blinq scanners? 😂

also my aunty says u can fix eyes by rubbing with turmeric. works better than any machine. trust me.

Nnaemeka Kingsley

December 4, 2025 AT 10:58Man, this is so important. In Nigeria, most kids never get checked at all. I’ve seen kids squinting in class, rubbing eyes all day - parents think it’s just tiredness. One boy I know, he couldn’t see the board, so he copied from his friend’s paper every day. He thought everyone saw like that. Imagine that.

Screening isn’t fancy - it’s just care. A quick look, a toy to follow, a light in the eye. That’s all. But in places with no doctors? We need mobile teams. We need teachers trained. Not gadgets. Just people who care.

Kshitij Shah

December 6, 2025 AT 06:10Oh wow, another American article that treats a 2-minute test like the second coming of Christ. Meanwhile, in India, we’ve been using ‘eye exercises’ and ‘Ayurvedic drops’ for centuries - and guess what? We still have engineers, astronauts, and Bollywood stars.

Maybe the problem isn’t the kids’ eyes - it’s the American obsession with turning every childhood quirk into a medical emergency. 🙄

Also, ‘bilingual staff’? We don’t need translators. We need fewer lawyers and more actual doctors.

Irving Steinberg

December 7, 2025 AT 12:15why do we even need this? my kid never had a screening and he’s fine. he reads books, plays video games, never bumps into stuff. stop making parents paranoid. also i hate when doctors make you do things just to make money. 🤷♂️

also why is everyone so obsessed with machines? i just look at my kid’s eyes. if they’re not crossed, they’re good. done.

Lydia Zhang

December 8, 2025 AT 10:00Screening is unnecessary. Kids adapt. They don’t need to see 20/32. They just need to see enough. This is overmedicalization. Also, the cost adds up. Why not just wait until they complain?

Kay Lam

December 10, 2025 AT 05:32I’ve been a pediatric nurse for 22 years, and let me tell you - the most heartbreaking thing isn’t the kids who fail the screen. It’s the parents who say, ‘But he’s fine, he just sits close to the TV.’

They don’t realize that their child’s brain has already started shutting down the input from one eye. That’s not laziness. That’s neurodevelopmental trauma. And it’s silent. No crying. No screaming. Just a quiet, irreversible loss of potential.

Every time we skip screening because ‘they’re too young’ or ‘they won’t cooperate,’ we’re not saving time - we’re stealing vision. And vision isn’t just about seeing the board. It’s about seeing the world. It’s about reading poetry, catching a ball, recognizing a face in a crowd, driving safely, seeing your child’s smile clearly when they’re grown.

We don’t need more gadgets. We need more awareness. We need more community outreach. We need more empathy. We need to stop thinking of this as a test and start thinking of it as a promise - a promise that every child, no matter their zip code, gets to see the world as it’s meant to be seen.

And if you’re a parent reading this - ask. Even if they say ‘no.’ Ask again. And again. Because your child’s eyes are not a suggestion. They’re a right.

Lucinda Bresnehan

December 10, 2025 AT 12:01I’m an optometrist, and I see this every day. Parents come in saying, ‘We didn’t know we needed this.’ I get it - no one teaches you this stuff. But here’s the truth: 70% of kids who fail screening have no obvious symptoms. That’s why we need universal screening.

Also, the red reflex test? It’s not just for cataracts. It catches retinoblastoma - a deadly childhood cancer. One flicker of white in the pupil? That’s not a reflection. That’s a tumor. And if caught early? 95% survival rate.

Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t wait for school to notice. Ask at your 12-month checkup. Even if they say ‘no.’ Ask again at 18 months. And again at 24. It takes 30 seconds. It could save a life.

Shannon Gabrielle

December 10, 2025 AT 22:22Oh great. Another woke, overpriced, corporate-sponsored panic. The government wants to turn every kid into a lab rat with a blinq™ scanner strapped to their forehead. Next they’ll be scanning for ‘emotional refractive errors’ and prescribing ‘vision therapy’ for anxiety.

And let’s not forget - 25% of screenings are wrong. So now we’re traumatizing kids with invasive tests just so some tech company can sell $5,000 machines to school districts that can’t afford paper towels.

Also, ‘Hispanic and Black children are less likely to be screened’? Maybe because their parents don’t trust this medical-industrial complex? You think a $2.5M research grant is going to fix systemic racism? LOL. Go fix the food deserts first.

ANN JACOBS

December 11, 2025 AT 14:46It is with the utmost reverence for the sanctity of human development, and with profound gratitude for the scientific rigor of contemporary pediatric ophthalmology, that I must express my unequivocal endorsement of the imperative to institutionalize comprehensive vision screening protocols for all children between the ages of three and five years, as this represents not merely a clinical intervention, but a metaphysical affirmation of the child’s inherent right to perceive the world in its full chromatic, spatial, and cognitive totality.

Furthermore, the integration of AI-driven instrumentation such as the blinq™ scanner into the primary care ecosystem constitutes a paradigmatic evolution in preventive health architecture - one which, if adopted uniformly across all socioeconomic strata, may serve as a foundational pillar in the construction of a more equitable, luminous, and visually just society.

Let us not be the generation that allowed the darkness of neglect to eclipse the light of potential.

Jeremy Butler

December 12, 2025 AT 04:23One cannot help but observe that the entire discourse surrounding pediatric vision screening is predicated upon a metaphysical assumption - namely, that the child’s visual cortex is a tabula rasa, malleable only within a narrow developmental window. But is this window truly fixed? Or is it a construct of medical orthodoxy, designed to legitimize interventionism?

Consider: if the brain can rewire itself after trauma, after stroke, after sensory deprivation - why must we assume that amblyopia is irreversible after age seven? Are we not, in fact, imposing a dogma of neuroplasticity’s limits - one that serves institutional convenience more than biological truth?

Perhaps the real crisis is not in the child’s eye, but in our refusal to entertain the possibility that healing may not be bound by arbitrary timelines.

Courtney Co

December 13, 2025 AT 23:02I’m a mom of three, and I just want to say - this post made me cry. I didn’t know my son had a lazy eye until he was 6. We never got screened. He’s fine now with glasses, but I wish I’d known sooner. I feel so guilty. Why didn’t anyone tell me? I didn’t even know what ‘red reflex’ meant. Can someone send me a link to the free training modules? I want to help other moms. I’m so sorry I didn’t ask sooner.