When you take a medication, you expect it to help-not hurt. But sometimes, even the right drug at the right dose can cause harm. These unwanted effects are called adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and they’re more common than most people realize. About 1 in 5 hospital admissions in the U.S. are linked to ADRs, and nearly 9 out of 10 of those are predictable. That’s where the Type A and Type B classification system comes in. It’s not just academic jargon-it’s the backbone of how doctors and pharmacists decide if a drug is safe for you, how to monitor for trouble, and when to stop it before something serious happens.

What Are Type A Adverse Drug Reactions?

Type A reactions are the everyday side effects you hear about in drug commercials. They’re predictable, dose-dependent, and tied directly to how the drug works in your body. Think of them as the drug doing too much of its job. For example, if you take a blood pressure pill and your pressure drops too low, that’s a Type A reaction. Same with nausea from antibiotics or drowsiness from antihistamines. These aren’t rare. About 85% to 90% of all adverse reactions fall into this category.What makes Type A reactions different is that they follow a clear pattern: the higher the dose, the worse the effect. If you double the dose, you roughly double the risk. That’s why doctors start with low doses and go up slowly-they’re trying to find the sweet spot where the drug works without overwhelming your system.

Common examples:

- Stomach upset from NSAIDs like ibuprofen (affects 15-30% of users)

- Liver damage from taking more than 4,000 mg of acetaminophen in a day

- Low blood sugar from insulin or sulfonylureas in diabetics

- Excessive bleeding from warfarin if the dose isn’t monitored

These reactions are usually mild, but they can turn serious if ignored. That’s why monitoring matters. If you’re on a drug known for Type A effects, your doctor will likely check your blood pressure, kidney function, or liver enzymes regularly. The goal isn’t to avoid the drug-it’s to use it safely.

What Are Type B Adverse Drug Reactions?

Type B reactions are the wild cards. They’re rare, unpredictable, and have nothing to do with how much of the drug you take. You could take the exact same dose as someone else and have no issues-while they end up in the ER. That’s because Type B reactions are usually caused by your body’s unique biology: your genes, your immune system, or how your liver processes the drug.These reactions make up only 5% to 10% of all ADRs-but they’re responsible for about 30% of hospitalizations and serious outcomes. That’s why they’re so dangerous. You can’t predict them with dose adjustments or routine tests. You can only spot them early and get the drug out of your system fast.

Examples of Type B reactions:

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome from sulfonamides or allopurinol-severe skin blistering that can be fatal

- Malignant hyperthermia triggered by anesthesia in people with a genetic muscle disorder

- Drug-induced lupus from medications like hydralazine or procainamide

- Anaphylaxis to penicillin-a life-threatening allergic reaction that can happen within minutes

Unlike Type A, there’s no safe dose for Type B. Even one pill can trigger it. That’s why doctors ask about past drug reactions, family history, and allergies before prescribing. If you’ve had a severe rash with one antibiotic, you’re likely at higher risk for the same with another-even if they’re in different classes.

Type A vs Type B: The Key Differences

It’s not enough to know what each type is-you need to know how they’re different. Here’s a breakdown of the seven most important contrasts:| Feature | Type A | Type B |

|---|---|---|

| Predictability | High-based on pharmacology | Low-no way to predict who will react |

| Dose dependence | Yes-worse with higher doses | No-even tiny doses can trigger it |

| Frequency | 85-90% of all ADRs | 5-10% of all ADRs |

| Severity | Usually mild | Often severe or fatal |

| Onset | Quick-hours to days | Variable-days to weeks |

| Prevention | Dose adjustment, monitoring | Avoidance in susceptible individuals |

| Mortality rate | Less than 5% | 25-30% |

This table isn’t just a reference-it’s a decision tool. If you’re starting a new drug and the patient has a history of severe reactions, you assume Type B until proven otherwise. If they’re elderly or on multiple meds, you watch for Type A. The difference changes how you manage risk.

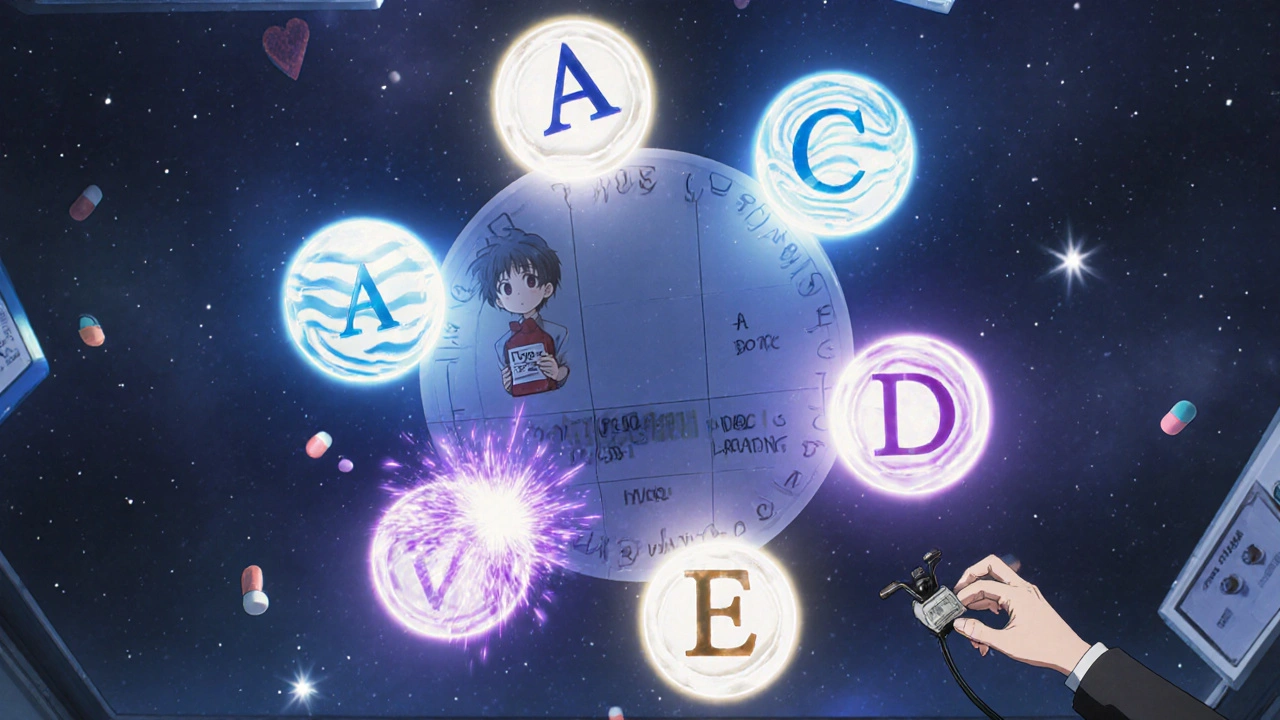

The Expanded Six-Type System (A-F)

The Type A and Type B system is useful, but it’s not enough for complex cases. That’s why experts use a six-type system that adds more detail:- Type C: Chronic effects from long-term use. Think osteoporosis from steroids taken for years, or adrenal suppression after taking prednisone for more than three weeks.

- Type D: Delayed reactions that show up years later. The classic example is diethylstilbestrol (DES)-a drug given to pregnant women in the 1950s to prevent miscarriage. Decades later, their daughters developed a rare vaginal cancer.

- Type E: Withdrawal effects. If you stop opioids, benzodiazepines, or even antidepressants too quickly, you can get rebound symptoms like anxiety, seizures, or high blood pressure.

- Type F: Therapeutic failure. This isn’t a side effect-it’s when the drug stops working because of another drug or a genetic issue. For example, rifampin can make birth control pills useless, leading to unintended pregnancy.

These categories matter because they change how you respond. Type C needs long-term monitoring. Type D requires asking about past exposures-even years ago. Type E means you can’t just stop a drug cold turkey. And Type F? That’s a missed diagnosis if you blame the patient for “not responding.”

According to a 2022 European Medicines Agency report, 92% of pharmacovigilance centers now use the six-type system for serious cases. It’s not just for specialists-it’s becoming standard in hospitals and clinics.

Why the Immunological System Matters Too

Not all Type B reactions are the same. Some are immune-driven. That’s where the Types I-IV system comes in:- Type I (IgE-mediated): Immediate allergic reactions-like anaphylaxis to penicillin. Happens within minutes to hours.

- Type II (Cytotoxic): Antibodies attack your own cells. Example: drug-induced hemolytic anemia from methyldopa or penicillin.

- Type III (Immune complex): Drug-antibody complexes build up and cause inflammation. Think serum sickness from cefaclor-fever, joint pain, rash.

- Type IV (Delayed cell-mediated): T-cells react slowly. This is the most common type of drug rash-like the red, itchy spots from amoxicillin in kids.

Knowing the subtype helps with diagnosis and treatment. Type I needs epinephrine. Type IV might just need time and antihistamines. Type II and III can require steroids or plasma exchange. The immunological system doesn’t replace Type A/B-it complements it.

What Clinicians Really Think

A 2022 survey of over 1,200 doctors found that 78% found the Type A/B system “moderately useful” but not enough on its own. Why? Because real life is messy.Take carbamazepine and hyponatremia (low sodium). Is that Type A or Type B? Some studies show it’s dose-related-so Type A. But others show it happens in certain genetic groups regardless of dose-so Type B. The answer? It’s both. About 15% of reactions don’t fit neatly into either box.

Doctors say the biggest challenge is telling the difference between a drug reaction and a worsening disease. Is that rash from the antibiotic-or from the underlying infection? Is that confusion from the statin-or from early dementia?

And then there’s Type F. A 2023 FDA report found that 25% of cases where a drug “didn’t work” were actually due to drug interactions-not patient noncompliance. That’s a huge missed opportunity.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

The field is evolving fast. Pharmacogenomics-the study of how genes affect drug response-is turning some Type B reactions into Type A. For example, we now know that people with the HLA-B*15:02 gene are at high risk for carbamazepine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Test for the gene before prescribing? That’s no longer experimental-it’s recommended.The FDA updated its reporting guidelines in 2023 to require detailed mechanistic classification for all serious Type B reactions. The World Health Organization is testing systems that link genetic data directly to ADR alerts in electronic health records.

By 2027, experts predict that 60% of reactions once called “idiosyncratic” will have known genetic triggers. That means fewer surprises. But it also means more testing-and more responsibility for prescribers to know when to order it.

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) is set to make the six-type system the global standard by late 2025. That’s a big deal. It means doctors in Tokyo, Berlin, and Chicago will all be speaking the same language when reporting drug reactions.

What You Need to Do

If you’re a patient:- Keep a list of every drug you’ve taken-and any reaction you had, even if it was mild.

- Ask: “Is this a common side effect, or something I should watch for?”

- Don’t assume a reaction was “just a coincidence.” Report it.

If you’re a clinician:

- Start with Type A-ask: Is this dose-related? Can I adjust it?

- If it’s sudden, severe, or doesn’t fit-think Type B. Stop the drug.

- Use the six-type system for documentation, especially for serious cases.

- Know when to order genetic testing-for drugs like abacavir, carbamazepine, or allopurinol.

The bottom line? Not all side effects are created equal. Understanding the difference between Type A and Type B isn’t just for pharmacologists. It’s for anyone who takes medication-and the people who prescribe it. The right classification saves lives. It prevents unnecessary stops. It helps you know when to worry-and when to let it go.

Are Type A reactions always mild?

No. While most Type A reactions are mild, like nausea or dizziness, they can become life-threatening if not managed. For example, an overdose of acetaminophen can cause fatal liver failure, and excessive anticoagulation from warfarin can lead to uncontrolled bleeding. The key difference isn’t severity-it’s predictability and dose dependence. Type A reactions can be prevented by adjusting the dose or monitoring closely.

Can you have a Type B reaction on your first dose?

Yes. Unlike allergies that develop after repeated exposure, some Type B reactions-especially immune-mediated ones like anaphylaxis or Stevens-Johnson syndrome-can occur the very first time you take the drug. This is because your immune system may already be primed by prior exposure to a similar molecule (like a virus or environmental trigger) that mimics the drug. There’s no need to have taken the drug before to react to it.

Why are Type B reactions harder to detect in clinical trials?

Clinical trials involve thousands of people, but not enough to catch reactions that occur in 1 in 10,000 or 1 in 100,000 patients. Type B reactions are rare by definition, and they often require specific genetic or immune conditions to trigger. That’s why most serious Type B reactions are only discovered after a drug is approved and used by millions of people in the real world-through post-marketing surveillance systems like MedWatch.

Is a drug allergy always a Type B reaction?

Most drug allergies are Type B, but not all Type B reactions are allergies. Type B includes both immune-mediated reactions (like anaphylaxis) and non-immune idiosyncratic reactions (like malignant hyperthermia or liver failure from halothane). An allergy specifically involves the immune system-so it’s a subset of Type B. But you can have a severe, unpredictable reaction without any immune involvement.

Can genetic testing prevent Type B reactions?

Yes, for some. Testing for the HLA-B*15:02 gene before prescribing carbamazepine can prevent Stevens-Johnson syndrome in people of Asian descent. Testing for HLA-B*57:01 before abacavir reduces the risk of a severe hypersensitivity reaction from 5% to near zero. These are proven, guideline-recommended practices. But genetic testing doesn’t cover all Type B reactions-only the ones with known markers. Research is expanding this list every year.

What’s the difference between a side effect and an adverse drug reaction?

All adverse drug reactions are side effects, but not all side effects are adverse. A side effect is any effect the drug has beyond its intended purpose-some are harmless, like dry mouth from antihistamines. An adverse drug reaction is a side effect that causes harm, requires medical attention, or leads to stopping the drug. The key is whether it’s harmful, not just noticeable.

Chrisna Bronkhorst

November 11, 2025 AT 10:53Type A reactions are the boring predictable ones but Type B? That’s where the real horror stories live. I saw a guy go into SJS from a single dose of allopurinol. No warning. No dose issue. Just pure bad luck with his HLA type. One pill and his skin started peeling. That’s not a side effect. That’s a biological betrayal.

Eve Miller

November 12, 2025 AT 04:36You misspelled 'pharmacogenomics' in the third paragraph. Also, 'idiosyncratic' is not a synonym for 'random.' And please, for the love of all that is clinical, stop using 'Type F' as if it's a real category. It's not in the original classification. This article reads like a blog post written by someone who watched one TED Talk.

manish kumar

November 13, 2025 AT 00:48I work in a rural clinic in India and I can tell you Type A reactions are the daily grind-nausea from metformin, dizziness from beta blockers, hypoglycemia from glibenclamide. We adjust doses, we monitor, we educate. But Type B? That’s the one that stops you cold. Last month, a young woman developed DRESS syndrome after taking nevirapine. She’d never had a rash before. No family history. No red flags. Just a gene she didn’t know she carried. We stopped the drug. She lived. But we almost lost her. That’s why I’m screaming from the rooftops: genetic screening isn’t luxury. It’s survival. And if your hospital still doesn’t test for HLA-B*57:01 before abacavir, you’re playing Russian roulette with your patients’ lives.

Amie Wilde

November 14, 2025 AT 03:41type b is why i stopped taking sulfa drugs. one rash and i was done. no second chances.

Mark Rutkowski

November 15, 2025 AT 14:48It’s funny how we treat drugs like they’re neutral tools. But every pill is a conversation between chemistry and chaos. Type A is the predictable argument-volume up, volume down. Type B? That’s the silent scream of your own biology saying ‘this doesn’t belong here.’ Maybe the real question isn’t how to classify reactions-but how to listen better before the body has to scream.

Ryan Everhart

November 15, 2025 AT 21:53so we’re now classifying drug failures as type f? next they’ll make type g for when the doctor forgets to write the script. genius. absolute genius.

David Barry

November 17, 2025 AT 01:08the 6-type system is just a fancy way of saying we don’t really understand half of what’s happening. type c d e f? those are just the leftovers we couldn’t fit into a or b. stop pretending this is science. it’s taxonomy with a placebo effect.

Alyssa Lopez

November 18, 2025 AT 12:35if you're not testing for hla alleles before prescribing you're not a doctor you're a gamble dealer. usa leads in pharmacovigilance and we still let this slide? shame.

Alex Ramos

November 18, 2025 AT 20:53biggest thing people miss: type a reactions are often ignored because they’re ‘mild.’ but chronic low-grade liver stress from NSAIDs? That’s how cirrhosis sneaks up on you. Don’t brush it off. Track it. Tell your doc. Your liver doesn’t text you when it’s dying.

vanessa k

November 20, 2025 AT 10:22my mom had drug-induced lupus from hydralazine. they didn’t even know it was the drug until she was in the hospital for 3 weeks. they thought it was rheumatoid. if this guide had been around back then… maybe she wouldn’t have lost her kidneys. thank you for writing this. it’s not just info. it’s a warning.

Nicole M

November 22, 2025 AT 03:31so if type b can happen on the first dose, does that mean allergies aren’t always from repeated exposure? that’s wild. i always thought you had to be sensitized first.

Arpita Shukla

November 23, 2025 AT 08:03you forgot to mention that type b reactions are more common in women. estrogen modulates immune response. studies show 60-70% of idiosyncratic reactions occur in females. this is critical for prescribing. yet no one talks about it. just like how most clinical trials are still male-dominated. classic.

edgar popa

November 24, 2025 AT 05:11type a = you knew it was coming

type b = you didn’t see it coming

type f = you thought they weren’t taking it

Gary Hattis

November 25, 2025 AT 06:43I’ve worked in ERs from Chicago to Nairobi. Type A? We fix it. Type B? We stabilize and pray. But the real tragedy isn’t the reaction-it’s the silence after. Patients don’t report rashes. Doctors don’t connect the dots. Systems don’t track. We’re drowning in data but starving for insight. This guide? It’s not academic. It’s a lifeline. Share it. Teach it. Make it part of every med student’s first week.

Renee Ruth

November 26, 2025 AT 22:56type b reactions are why i’m terrified of new meds. one time i got a rash from a generic version of a drug i’d taken for years. turned out the filler was different. not the active ingredient. the filler. so now i refuse generics. i don’t care if it costs 10x more. my skin is not a lab experiment.