When someone has liver disease, taking opioids isn't as simple as it seems. The liver doesn't just filter toxins-it's the main factory that breaks down these drugs. When it's damaged, that factory slows down or shuts off in parts, and opioids start building up in the body. This isn't just a minor concern. It can lead to dangerous side effects, even at normal doses. People with cirrhosis, fatty liver, or alcohol-related damage often don't realize their pain meds are becoming more potent, not less.

How the Liver Normally Processes Opioids

The liver uses two main systems to break down opioids: the cytochrome P450 enzymes and glucuronidation. These are like specialized assembly lines. CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 are the most common enzymes involved. They chop up drugs like oxycodone and fentanyl into smaller pieces so the body can flush them out. Glucuronidation, handled by UGT enzymes, adds a sugar molecule to drugs like morphine to make them water-soluble for kidney excretion.

In a healthy liver, this system works fast. Oxycodone, for example, has a half-life of about 3.5 hours-meaning half the drug is gone from your blood in that time. Morphine turns into two metabolites: morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G), which helps with pain, and morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G), which can cause seizures and confusion. Both get cleared quickly.

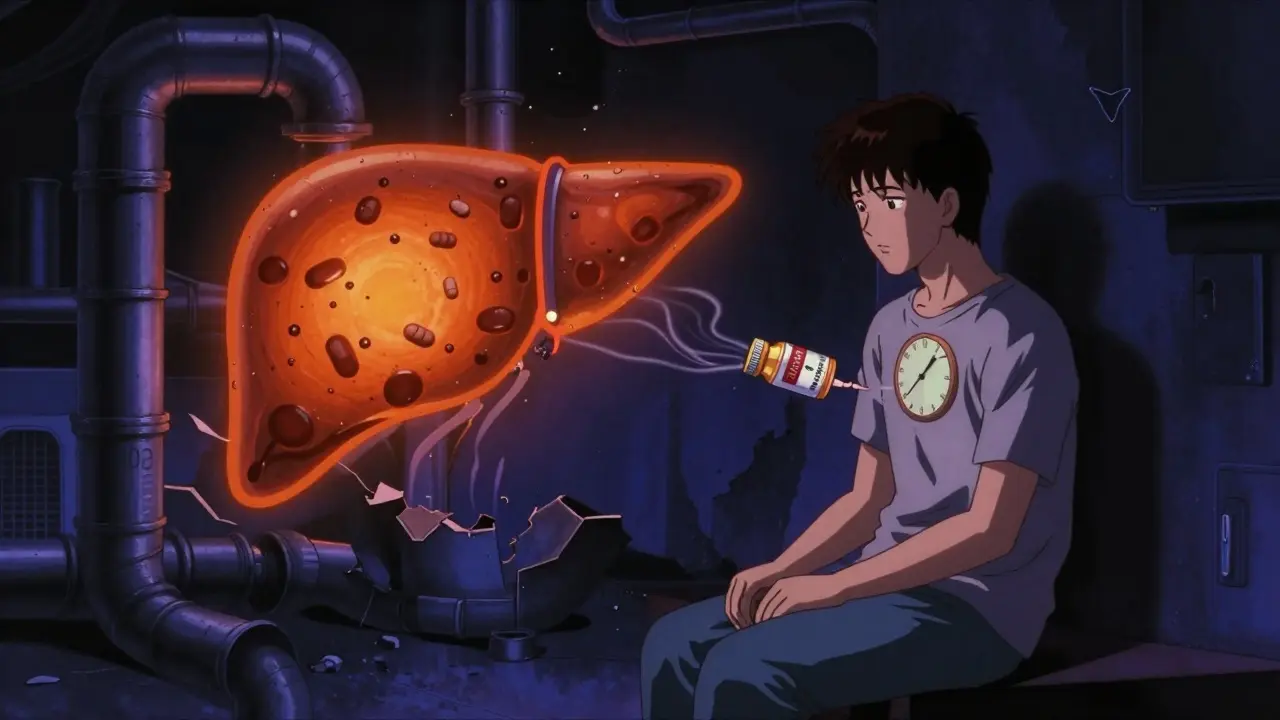

What Happens When the Liver Fails

In liver disease, these pathways break down. The more severe the damage, the worse it gets. In advanced cirrhosis, CYP3A4 activity drops by up to 70%. That means drugs like oxycodone aren’t broken down fast enough. Studies show the maximum concentration of oxycodone in the blood can rise by 40%, and its half-life stretches from 3.5 hours to as long as 24.4 hours. That’s more than six times longer. The drug sticks around, and every dose piles on top of the last.

Morphine is even riskier. In healthy people, M6G and M3G are cleared within hours. In liver failure, clearance drops by 50-80%. M6G builds up, increasing pain relief-but so does M3G. And M3G doesn’t just sit there. It crosses the blood-brain barrier and can trigger seizures, muscle twitching, and hallucinations. A patient on a stable morphine dose might suddenly start having neurological symptoms, not because they took more, but because their liver can’t keep up.

Why Some Opioids Are Riskier Than Others

Not all opioids are created equal when the liver is damaged. Morphine is one of the most dangerous because it relies almost entirely on glucuronidation. If that pathway is impaired, toxic metabolites pile up. Oxycodone is also risky-it depends on two enzymes, and if either one slows down, levels spike. Fentanyl and hydromorphone are metabolized differently, but data is still limited.

Methadone is a gray area. It’s broken down by multiple enzymes, which sounds like a good thing. But because it’s metabolized by so many pathways, there’s no clear way to predict how liver disease affects it. Dosing guidelines simply don’t exist. Some doctors use it anyway, but they’re guessing.

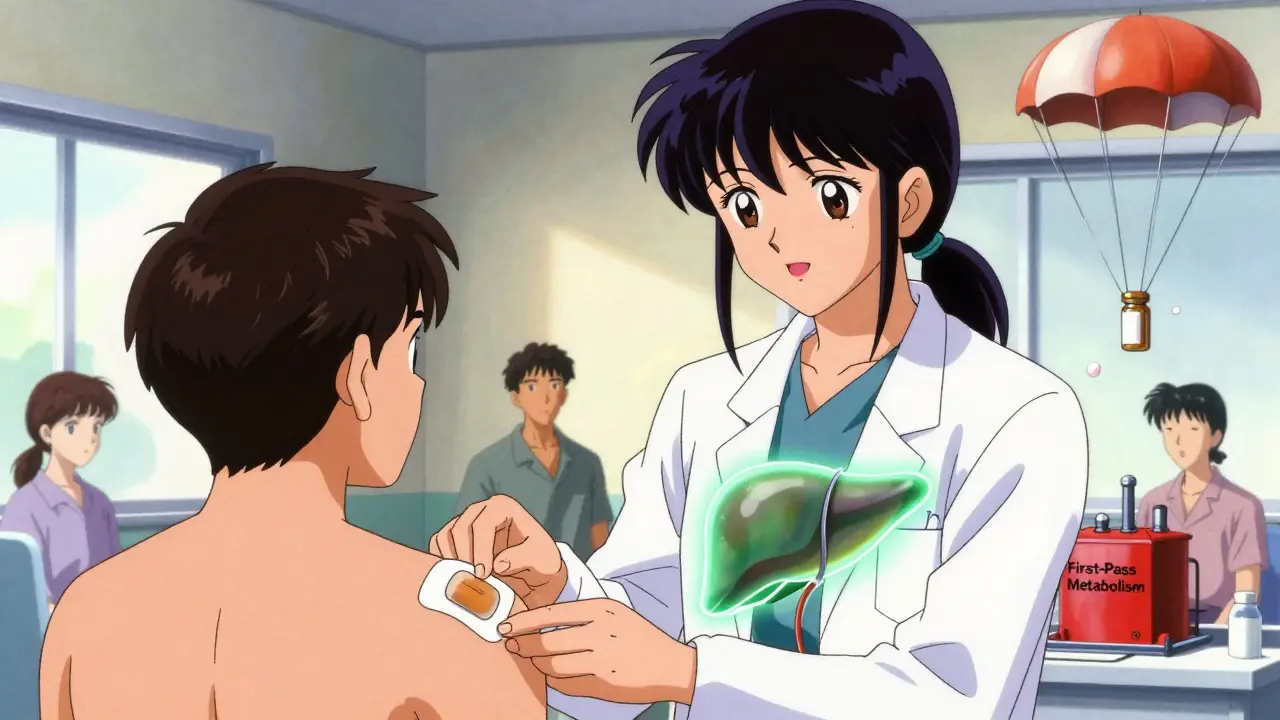

Transdermal options like fentanyl patches or buprenorphine skin patches might be safer because they bypass the liver entirely. The drug enters the bloodstream through the skin, avoiding first-pass metabolism. That’s why experts increasingly recommend patches for patients with moderate to severe liver disease-when pain control is needed.

Chronic Use Makes Liver Damage Worse

It’s not just about the drugs building up. Long-term opioid use can actually make liver disease worse. Opioids change the gut microbiome-the trillions of bacteria living in your intestines. This disruption weakens the gut barrier, letting toxins leak into the portal vein and head straight to the liver. These toxins trigger inflammation, which accelerates scarring in fatty liver disease, hepatitis, or cirrhosis.

Studies show patients with alcohol-related liver disease who use opioids long-term have faster progression to cirrhosis than those who don’t. The same pattern appears in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The liver isn’t just struggling to process the opioid-it’s being attacked by the opioid’s side effects.

Dosing Adjustments You Can’t Ignore

There are clear, evidence-based rules for adjusting opioid doses in liver disease-but they’re rarely followed. For morphine: if liver function is mildly impaired, reduce the dose by 25-50% but keep the same dosing interval. If it’s severe, cut the dose by 50-75% AND extend the time between doses (e.g., every 8 hours instead of every 4).

For oxycodone: start at 30-50% of the usual dose in severe liver impairment. Never start at full dose. Monitor closely for drowsiness, slow breathing, or confusion. Even a small dose can be enough to cause respiratory depression in someone with advanced cirrhosis.

There’s no safe starting dose for methadone in liver disease. Avoid it unless absolutely necessary-and even then, only with frequent blood level monitoring, which most clinics don’t do.

What We Still Don’t Know

Here’s the problem: we have solid data on morphine and oxycodone. But for buprenorphine, tapentadol, and tramadol, there’s almost nothing. We don’t know how much these drugs accumulate. We don’t know if their metabolites are toxic. And we don’t have guidelines for dosing them in patients with NAFLD, hepatitis C, or autoimmune liver disease.

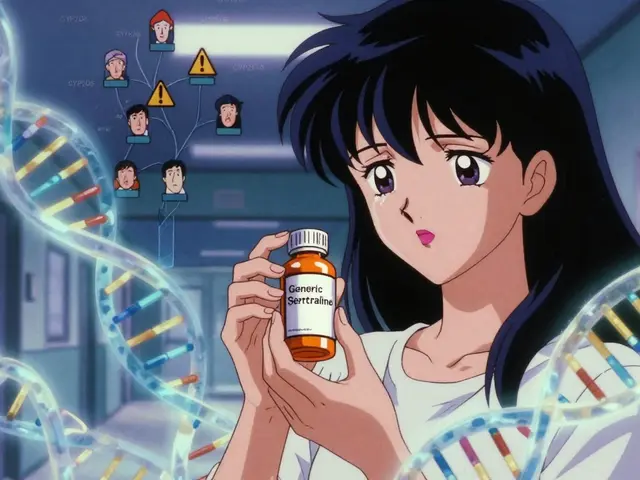

Also, we don’t know how liver disease affects opioids differently based on the cause. For example, CYP2E1 activity goes up in alcohol-related liver disease, which might make some drugs break down faster. But in fatty liver disease, CYP3A4 drops, slowing others down. That means two patients with the same diagnosis-say, “liver cirrhosis”-could have completely different responses to the same opioid.

What Clinicians Need to Do

Doctors need to stop assuming liver disease means “lower pain tolerance.” It means “higher risk of overdose.” They need to:

- Choose opioids with less liver dependence-patches over pills when possible

- Start low, go slow, and monitor for neurological side effects

- Use Child-Pugh or MELD scores to guide dosing, not just patient weight

- Avoid morphine in advanced disease

- Never use methadone without a hepatology consult

- Watch for signs of opioid-induced gut dysfunction: bloating, constipation, nausea

Pain management in liver disease isn’t about giving more drugs. It’s about giving smarter ones-and less of them. The liver doesn’t just metabolize opioids. It protects you from them. When it’s damaged, the protection is gone.

Joseph Charles Colin

February 8, 2026 AT 10:36The liver's metabolic pathways for opioids are far more complex than most clinicians realize. CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 polymorphisms alone can cause 300% variability in clearance, and when combined with cirrhosis-induced downregulation, you're essentially playing Russian roulette with dosing. Morphine's M3G metabolite isn't just neurotoxic-it's a delayed-action bomb that accumulates silently. Most ERs still don't screen for it because the assays aren't routine. We need mandatory pharmacokinetic modeling before prescribing opioids in any stage of liver disease.

John Sonnenberg

February 8, 2026 AT 21:32And yet-people still get oxycodone prescriptions like it's aspirin. I had a cousin with Child-Pugh B cirrhosis on 30mg q4h. She was lucid at first. Then, one morning, she started talking to the ceiling fan like it was her dead mother. No one connected it to the pain meds. By the time they stopped it, she’d had two tonic-clonic seizures. This isn’t theoretical. This is real. And it’s happening every single day.

Joshua Smith

February 9, 2026 AT 11:39This is such an important post. I’ve been working in hospice for over a decade, and I’ve seen how easily liver impairment gets overlooked in pain management. The shift from pills to patches-especially buprenorphine-isn’t just safer, it’s more dignified. Patients don’t have to worry about swallowing pills when their GI motility is already compromised. Small changes make a huge difference in quality of life.

Jessica Klaar

February 10, 2026 AT 22:17I work with a lot of patients who have hepatitis C and chronic pain. Many of them were told by their primary care doctors that opioids were 'fine' as long as they didn't 'overdo it.' But 'overdoing it' is impossible when your liver can't process it. I’ve had patients cry because they thought they were being 'addicts' for needing help-when really, their bodies were just failing them. We need more compassion and less judgment in these conversations.

Randy Harkins

February 12, 2026 AT 10:05Thank you for this. I’ve been advocating for this exact approach for years. The gut-liver axis is the missing piece in so many opioid guidelines. When toxins leak from a damaged barrier, it’s not just about metabolism-it’s about systemic inflammation. Opioids don’t just sit in the liver; they become part of the disease process. We need to stop treating pain in isolation. It’s always connected.

PAUL MCQUEEN

February 13, 2026 AT 04:39So… we’re just supposed to avoid opioids entirely? What about patients with cancer? Or severe trauma? Are we just going to let them suffer because some drug metabolism is 'complicated'? This feels like medical elitism dressed up as science.

glenn mendoza

February 13, 2026 AT 08:40Your insights are profoundly thoughtful. The notion that the liver serves as a protective barrier-rather than merely a metabolic organ-is both elegant and clinically urgent. I would respectfully suggest that this paradigm shift should be integrated into residency curricula nationwide. Our current training still treats hepatic impairment as a footnote in pharmacology.

Kathryn Lenn

February 14, 2026 AT 00:13Of course the pharmaceutical companies don’t want you to know this. They profit from pills. Patches? Not as profitable. And methadone? It’s generic. No one’s making billions off it. So they fund studies that ignore metabolite toxicity. They lobby guidelines committees. And then they tell doctors to 'use their judgment.' Meanwhile, patients are dying quietly. This isn’t medicine. It’s a business model.

John Watts

February 14, 2026 AT 01:58There’s hope here. I’ve seen patients with advanced NAFLD switch from oral oxycodone to buprenorphine patches-and suddenly, their liver enzymes improve. Their sleep improves. Their mood improves. It’s not magic. It’s physiology. When you remove the burden of first-pass metabolism and gut toxicity, the body can start healing. We just need to listen to the data instead of the old habits.

Chima Ifeanyi

February 15, 2026 AT 08:10Let’s be real: the entire opioid paradigm in hepatology is built on flawed assumptions. CYP3A4 suppression in cirrhosis? Data from 1998. MELD scores? Designed for transplant triage, not pharmacokinetics. We’re applying a blunt instrument to a scalpel problem. And now we’re surprised when patients overdose on 5mg of morphine? This isn’t a pharmacology issue-it’s a systemic failure of evidence-based medicine.

Tori Thenazi

February 16, 2026 AT 09:45Wait… so are you saying the government is hiding this? Because I’ve read that the CDC’s opioid guidelines were influenced by a pharmaceutical lobbyist who used to work for Purdue… and didn’t disclose it… and now they’re saying 'patches are safer'… but they don’t say why… and why is no one talking about how the FDA approved fentanyl patches without long-term liver studies…?

Elan Ricarte

February 17, 2026 AT 03:24Man, I’ve been in this game too long. I remember when we used to give morphine to cirrhotic patients like it was water. Then one guy coded in the ER and we found his M3G level was 12x normal. We didn’t even test for it back then. Now? We still don’t test. We just blame the patient. 'You didn’t follow instructions.' Bullshit. The instructions didn’t exist. The science didn’t exist. We were flying blind.

Ritteka Goyal

February 17, 2026 AT 22:40So I live in India and we don’t have much access to patches or blood tests. We give oral morphine because it’s cheap and available. My patients with cirrhosis? They get drowsy, then they get confused, then they stop eating. We call it 'liver coma.' But maybe… it’s just the morphine? I don’t know. We don’t have labs. We don’t have guidelines. We just hope they don’t die. It’s not science. It’s survival.

Andrew Jackson

February 19, 2026 AT 14:23It is an undeniable moral failing that we permit the continued prescription of morphine in patients with compromised hepatic function. The very notion of 'pain management' without regard for pharmacokinetic integrity is not medicine-it is negligence cloaked in clinical authority. The liver is not a mere accessory organ; it is the sentinel of metabolic integrity. To ignore its role is to invite catastrophe. We must institute mandatory pharmacogenetic screening before any opioid is prescribed to patients with any degree of liver dysfunction. Anything less is unconscionable.

Monica Warnick

February 20, 2026 AT 13:02I’ve been thinking about this all day. I work in a clinic where 60% of our patients have NAFLD. We give them hydrocodone because it’s what the formulary says. But what if… what if the real problem isn’t the pain? What if it’s the constipation? The bloating? The way they look at us like we’re the enemy? Maybe we’re making it worse. Maybe we’re the ones who should be scared.