Postoperative Ileus Recovery Calculator

Opioid Dose Calculator

Enter the total morphine milligram equivalents (MME) you received in the first 48 hours after surgery to estimate your bowel recovery time.

Why This Matters

Opioids are a primary cause of postoperative ileus (POI), which delays bowel function recovery. Studies show that:

- 2 days Recovery time for < 20 MME

- 5 days Recovery time for > 50 MME

- 50% difference in recovery time between low and high dose groups

Estimated Recovery Time

Important Note

Recovery times are estimates based on clinical studies. Individual results may vary based on surgery type, medical history, and other factors.

Enter your opioid dose to see your estimated recovery time.

Key Prevention Strategies

Pre-Op Pain Control

Start with acetaminophen (1g IV) and ketorolac before surgery

Limit Opioid Dose

Keep total opioids under 30 MME in first 24 hours

Early Mobility

Walk within 4 hours after surgery

Gum Chewing

Chew gum 4 times daily to stimulate bowel function

After surgery, many patients don’t just worry about pain-they worry about not pooping. It sounds simple, but postoperative ileus (POI) is one of the most common and frustrating complications after surgery. It’s not a bowel obstruction. It’s not an infection. It’s when your gut just stops working for a few days, and opioids are often the main reason why.

What Exactly Is Postoperative Ileus?

Postoperative ileus happens when your intestines slow down or stop moving food and gas through your system after surgery. You might feel bloated, nauseous, and unable to eat. You won’t pass gas or have a bowel movement for days. In some cases, it lasts longer than three days-which is when doctors start treating it as a real problem, not just a normal part of recovery.

This isn’t rare. Up to 30% of patients after abdominal surgery develop it. But even after hip or knee replacements, where you wouldn’t think gut function matters, POI still shows up in 15-25% of cases. And the biggest trigger? Opioids.

Why Opioids Make POI Worse

Opioids are great for pain. They bind to receptors in your brain and spinal cord to dull the sensation. But they also bind to receptors in your gut-specifically mu-opioid receptors on the nerves that control bowel movement. When they do, they shut down the natural rhythm of your intestines.

Studies show that just 5-10 mg of morphine per hour can delay gastric emptying by up to 200%. That means food sits in your stomach longer. Colonic motility drops by as much as 70%. You get hard, dry stools. You feel bloated. You strain. You might even get reflux. These aren’t just side effects-they’re direct results of how opioids interact with your digestive system.

And it’s not just the drugs you’re given. Your body releases its own opioids during surgery as part of the stress response. So even if you don’t get any pain meds, your gut is already being slowed down. Add prescription opioids on top, and it’s a double hit.

How Long Does It Last-and Why It Costs So Much

On average, patients with POI stay in the hospital 2-3 extra days. That’s not just uncomfortable-it’s expensive. In the U.S. alone, POI adds up to $1.6 billion in extra costs every year. Hospitals get penalized if patients are readmitted because of it. Insurance companies push back. And patients? They miss work, miss family time, and feel like their recovery is stuck.

One study of 1,247 patients found that those who got more than 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) in the first 48 hours took over five days to have their first bowel movement. Those who got less than 20 MME? Two days. That’s more than a 50% difference.

What Doesn’t Work

For years, doctors relied on nasogastric tubes-those big tubes shoved through the nose into the stomach-to relieve bloating. But research shows they don’t speed up recovery. They just make patients more uncomfortable. Same with just waiting it out. POI doesn’t get better on its own faster just because you do nothing.

Even chewing gum, which sounds silly, has been tested. And guess what? It works. Chewing gum tricks your brain into thinking you’re eating, which signals your gut to start moving again. Studies show patients who chewed gum four times a day had their bowels moving a full day sooner than those who didn’t.

What Actually Works: Prevention Strategies

The best way to handle POI is to stop it before it starts. And the key is reducing opioids-not eliminating them, but using them smarter.

- Start before surgery. Give acetaminophen (1g IV) and ketorolac (if no kidney issues or bleeding risk) before the cut. This lowers your pain right away so you need less opioids later.

- Use regional anesthesia. Spinal or epidural blocks can cut opioid use by half. One study showed orthopedic patients with spinal anesthesia had POI rates of just 8.5%, compared to 22.3% with general anesthesia and opioids.

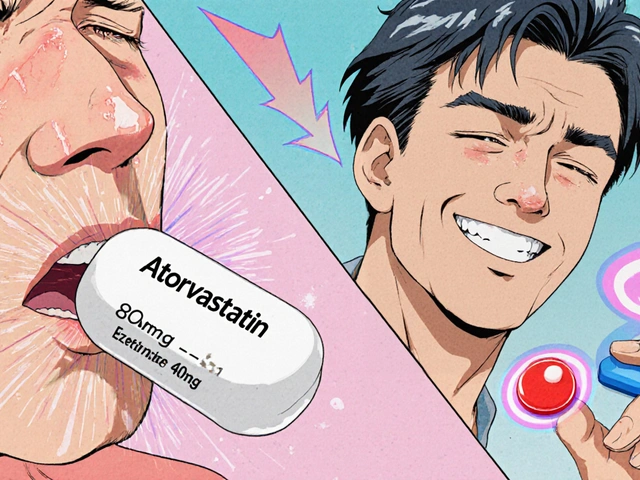

- Limit total opioid dose. The ERAS Society recommends keeping total opioid use under 30 MME in the first 24 hours. That’s about 3-4 doses of 10mg oxycodone. Stay under that, and POI drops from 30% to 18%.

- Get up and move. Walking within 4 hours after surgery reduces POI duration by 22 hours. Nurses who push early mobilization see better results than those who wait until the next day.

- Use non-opioid painkillers. Gabapentin, lidocaine patches, and NSAIDs can cover a lot of the pain without touching your gut.

When You Need Medication to Fix It

Even with prevention, some patients still develop POI. That’s where targeted drugs come in.

Alvimopan and methylnaltrexone are peripheral opioid antagonists. They block opioids in the gut but not in the brain. That means pain control stays intact, but your bowels start working again.

Alvimopan cuts recovery time by 18-24 hours in abdominal surgery patients. Methylnaltrexone works even faster in opioid-tolerant patients, speeding up bowel function by 30-40%. But they’re not for everyone. They’re expensive-around $150 per dose-and they’re dangerous if you actually have a bowel obstruction (which happens in less than half a percent of cases).

They’re most useful for high-risk patients: those having bowel surgery, those who’ve never taken opioids before, or those getting high doses. Routine use in low-risk patients doesn’t make economic sense.

Real-World Success Stories

Hospitals that treat POI like a system problem-not a patient problem-see dramatic results.

The University of Michigan implemented a POI bundle: pre-op acetaminophen, epidurals when possible, no routine NG tubes, gum chewing, and walking within 4 hours. Within a year, they cut average POI duration from 4.5 days to 2.7 days. Hospital stays dropped by 1.8 days. Each patient saved the system $2,300.

On the nursing floor, teams started doing daily “POI rounds.” Every morning, nurses checked: When did they pass gas? When did they have a bowel movement? Could they drink 1,000 mL without vomiting? If not, they triggered the next step-more mobility, less opioid, or a dose of methylnaltrexone.

One hospital in rural Ohio struggled for months. Nurses didn’t know how to mobilize patients safely. Anesthesiologists refused to give epidurals because “it’s not our job.” After six months of training, compliance hit 88%. POI rates dropped by 40%.

The Big Picture: Why This Matters

POI isn’t just about bowels. It’s about how we treat pain after surgery. For decades, opioids were the default. But we now know they’re a blunt tool for a complex problem.

There’s a growing gap between academic centers and rural hospitals. In teaching hospitals, 92% have formal POI protocols. In rural clinics, only 28% do. That means a patient having gallbladder surgery in a city might go home in three days. One in a small town might be stuck for five.

Regulators are catching on. CMS penalizes hospitals with high POI readmission rates. The FDA now requires opioid labels to warn about bowel dysfunction. And new research is coming fast: AI models are being tested to predict who’s at risk based on 27 pre-op factors-with 86% accuracy. Fecal transplants are being tried for stubborn cases. Naltrexone implants are in early testing.

By 2027, experts predict POI prevention will be standard of care. Not because it’s trendy-but because the data is undeniable. Less opioids. More movement. Better pain control. Faster recovery.

What Patients Should Ask

If you’re scheduled for surgery, ask these questions:

- Will I get regional anesthesia instead of general?

- What’s the plan for pain control after surgery? Will I get acetaminophen or ketorolac first?

- What’s the maximum opioid dose I’ll get in the first 24 hours?

- Will I be encouraged to walk the same day?

- Can I chew gum after surgery?

If your care team doesn’t have an answer, it’s not because they’re negligent. It’s because they haven’t been trained. But that’s changing. And now you know what to look for.

Stuart Shield

January 5, 2026 AT 18:13Man, this is one of those posts that makes you realize medicine isn’t just about cutting and stitching-it’s about listening to the whole body. I’ve seen patients stare at the ceiling for days because no one thought to ask if they’d chewed gum. Simple stuff, right? But it’s the simple stuff that gets buried under stacks of protocols and opioid prescriptions. Kudos to the hospitals actually doing the work.

Amy Le

January 6, 2026 AT 01:25US healthcare is finally waking up 😤👏 But why does it take a billion-dollar cost to get people to stop giving morphine like candy? We’ve known this for 20 years. 🤦♀️

Mukesh Pareek

January 7, 2026 AT 08:01Postoperative ileus is fundamentally a neurogastroenterological dysrhythmia precipitated by mu-opioid receptor agonism in the myenteric plexus, compounded by inflammatory cytokine-mediated enteric neuropathy. The key lies in multimodal analgesia with preemptive NSAIDs and regional blockade to attenuate central sensitization and preserve gut motility. Alvimopan, a peripherally restricted opioid antagonist, demonstrates statistically significant acceleration of GI transit in RCTs (p<0.01), though cost-effectiveness remains contentious in low-risk cohorts. Early ambulation and non-pharmacological neuromodulation via mastication are underutilized but physiologically sound interventions.

Pavan Vora

January 8, 2026 AT 12:18Wow, this is so true... I mean, I had my knee done last year, and they just gave me oxycodone and said, 'just wait it out'... I didn't poop for 5 days... I felt like a balloon... and no one even mentioned gum... I just chewed some old gum I had in my pocket... and like... 3 hours later... I felt something move... I think it was gas... but still... I was so relieved... 🤭

Lily Lilyy

January 9, 2026 AT 14:44This is so important. Every patient deserves to recover with dignity. Walking after surgery isn’t just good advice-it’s a right. And chewing gum? It’s free, safe, and it works. Let’s make this standard everywhere. You’ve given us hope.

Susan Arlene

January 10, 2026 AT 01:35so like... opioids = gut murder? yeah that tracks. i had a surgery last year and i swear my intestines went on strike. no one told me about the gum thing until i googled it at 3am. lol. also, why is everyone still giving 100mg of morphine like it’s candy? 🤷♀️

Rachel Wermager

January 10, 2026 AT 13:32Let’s be real: if you’re giving more than 30 MME in the first 24 hours, you’re not managing pain-you’re managing liability. The ERAS guidelines aren’t suggestions; they’re evidence-based mandates. The fact that rural hospitals still don’t have protocols is a systemic failure. And yes, alvimopan is expensive-but it’s cheaper than a 5-day hospital stay. The math is clear. Stop being cheap and start being smart.

Harshit Kansal

January 11, 2026 AT 07:19Bro I had this happen after my appendix came out and I thought I was dying. No gas for 4 days. Nurses kept saying 'it's normal'. I was like I'm not normal I'm a human being with a gut. Then I chewed some gum I stole from the vending machine and boom-like 2 hours later I was in the bathroom crying. Not from pain. From relief. That gum was my hero.

Vinayak Naik

January 13, 2026 AT 06:32Y’all need to stop treating pain like it’s a war and opioids are the nukes. I work in a small clinic in Kerala and we use paracetamol, ice packs, and get folks walking within 2 hours. No fancy drugs. No tubes. Just movement and kindness. POI? Rare. Patients go home happy. You don’t need a Harvard degree to do this. Just care.

Katelyn Slack

January 13, 2026 AT 07:44thank you for writing this. i’m a nurse and we just started doing the POI rounds last month. one old man told me he hadn’t passed gas since surgery and he was so embarrassed. we gave him gum and walked him down the hall. he smiled for the first time in days. small things matter.

Kiran Plaha

January 13, 2026 AT 19:26why is this even a thing? i mean, we know opioids slow the gut. why do we keep using them like they’re magic? i get pain is bad but maybe we need to stop pretending we’re helping by drowning people in drugs. i had a friend who got 80mg of morphine after a gallbladder thing and she was stuck in the hospital for a week. it was insane.

Brian Anaz

January 15, 2026 AT 15:03Another liberal medical fantasy. You want to cut opioids? Fine. But what happens when the patient is in agony? You gonna make them walk on a broken hip? This isn’t about 'protocols'-it’s about common sense. And if you think gum fixes everything, you’re delusional. This is America. We don’t chew gum to heal-we use science. And science says opioids work.